The purpose of this blog is to discuss the anatomy, mechanism of injury, assessment, and management of high ankle sprains, also referred to as syndesmosis injuries.

Looking to improve the strength, range of motion, and stability of your ankles to enhance your function and performance? Check out our Ankle Resilience program!

Anatomy

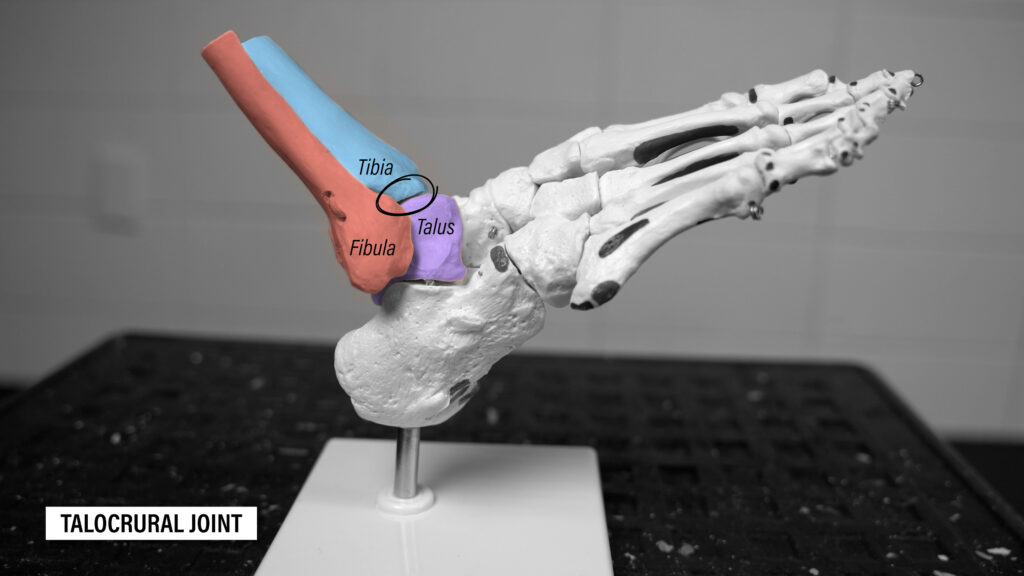

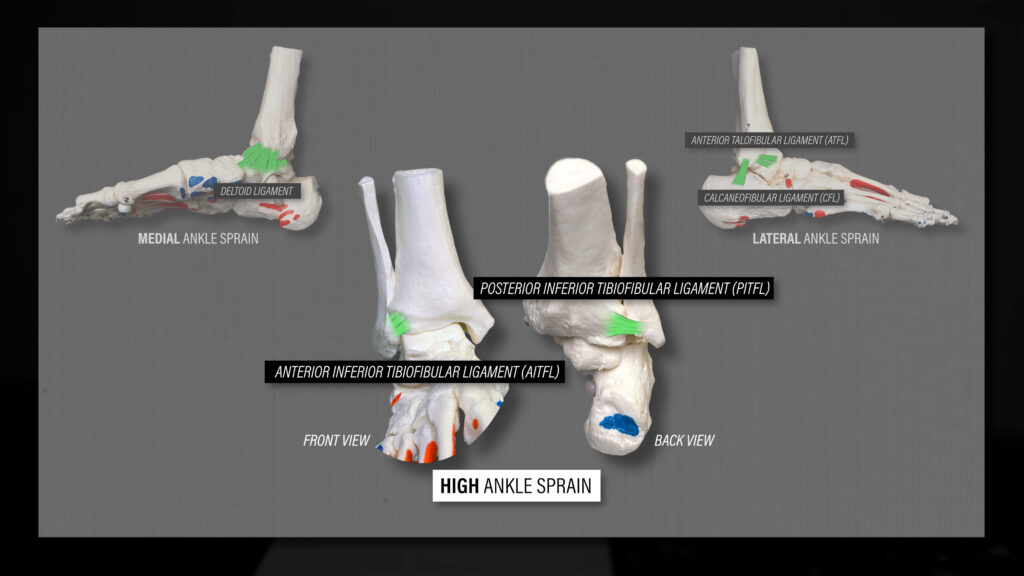

The ankle, also known as the talocrural joint, is the connection between the talus, tibia (shin bone/inner ankle bone), and fibula (outer ankle bone).

Since the talus is firmly positioned between the tibia and fibula, the primary motions that occur are plantar flexion (pointing your foot down) and dorsiflexion (bringing your foot up).

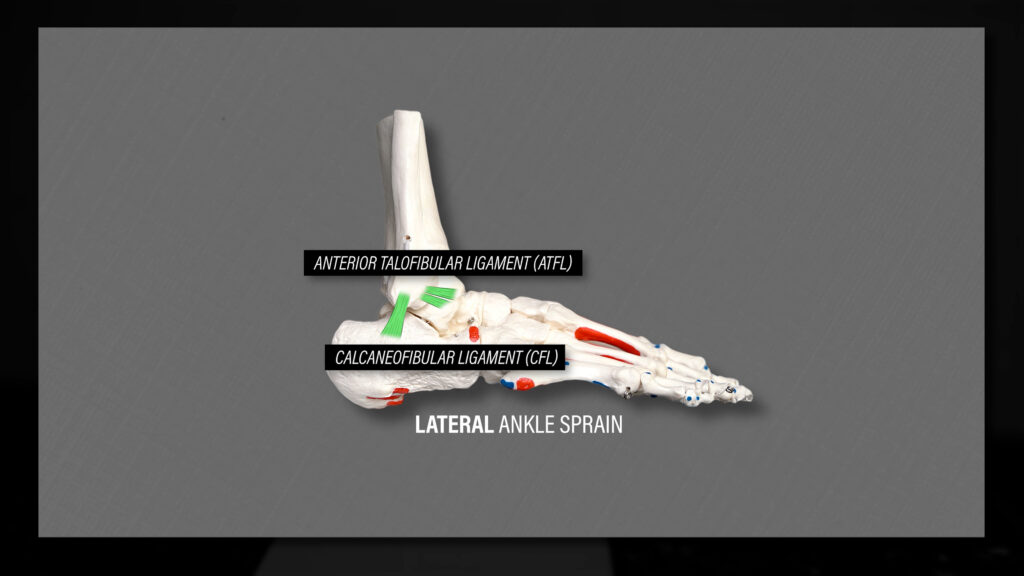

The ligaments that support the outer portion of the ankle are the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) and calcaneofibular ligament (CFL). These are the ligaments most often injured during a lateral ankle sprain.

The ligaments that support the inner portion of the ankle are collectively known as the deltoid ligament.

On the other hand, a high ankle sprain refers to an injury to the distal tibiofibular joint, which is the connection between the tibia and fibula.

The primary ligaments that support this joint are the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL) in front, the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PITFL) in back, and the interosseous ligament in between.

There are different types of joints in the body, and the distal tibiofibular joint is a syndesmosis. Therefore, medical doctors and other healthcare professionals will usually call this a syndesmosis injury as opposed to a high ankle sprain.

High Ankle Sprain / Syndesmosis Injury

Unlike a lateral ankle sprain in which you twist or roll your ankle, a syndesmosis injury occurs when your foot is planted, your ankle is dorsiflexed, and your foot is rotating outward relative to your tibia. The majority of injuries involve contact, such as being tackled in football. Click here for a video.

Normally when you dorsiflex your ankle, the tibia and fibula separate a bit to allow for movement of the talus. However, when a significant rotation component is added, which the joint isn’t structured for, the talus forces the fibula to peel away from the tibia.

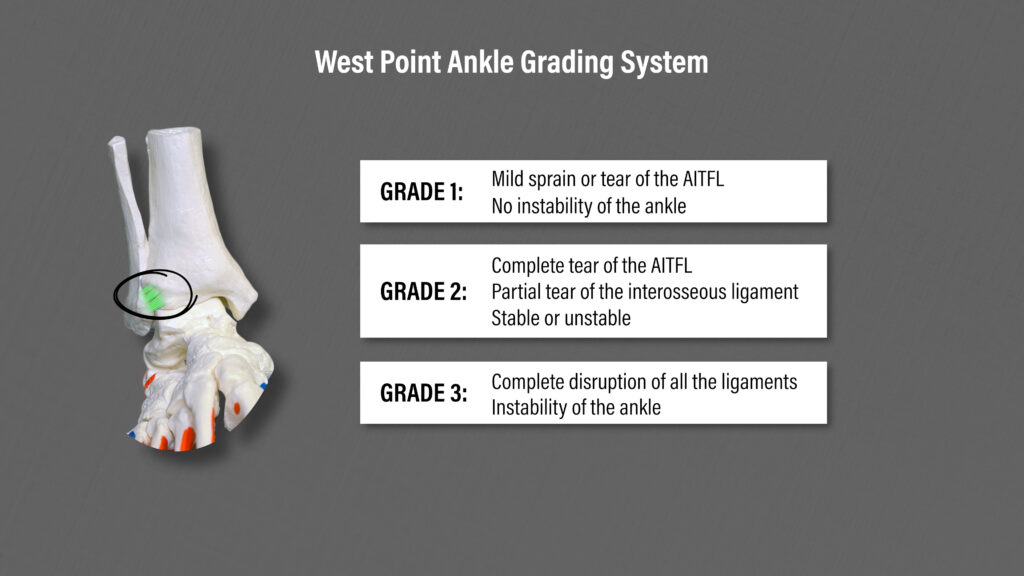

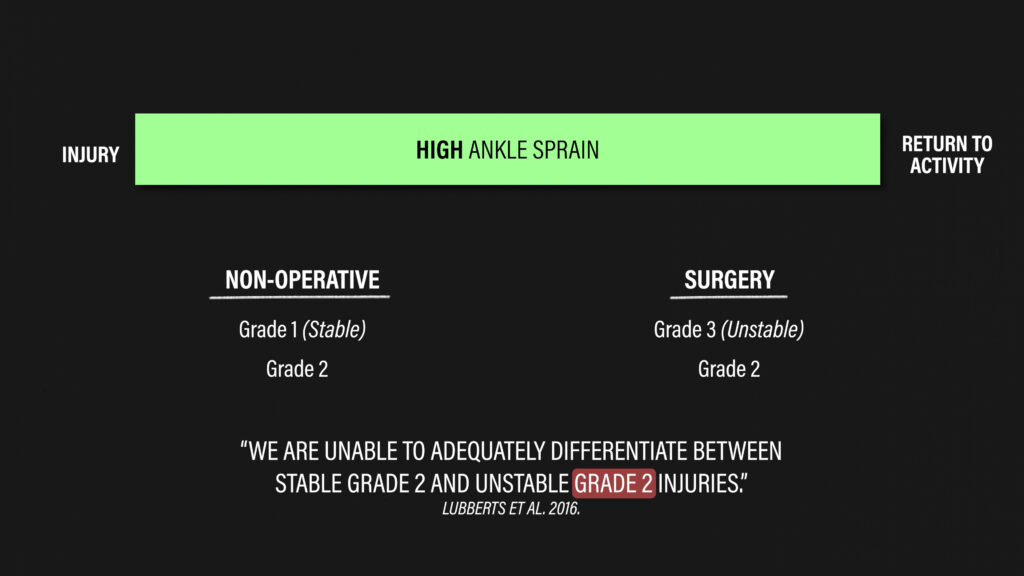

There’s a variety of classification systems used to grade the severity of the injury, but I’ll use the West Point Ankle Grading System since it’s simple and one of the most popular.

- Grade 1: mild sprain or tear of the AITFL with no instability of the ankle

- Grade 2: complete tear of the AITFL and partial tear of the interosseous ligament; may be stable or unstable

- Grade 3: complete disruption of the ligaments resulting in instability of the ankle

Due to the high-force mechanism of injury, it’s also possible for disruption of the deltoid ligament and fractures to occur.

High Ankle Sprain Assessment

In a professional or collegiate sports setting, injuries are usually assessed quickly by a medical doctor or athletic trainer, so this information will be presented as if it’s been at least 5-7 days since the initial incident.

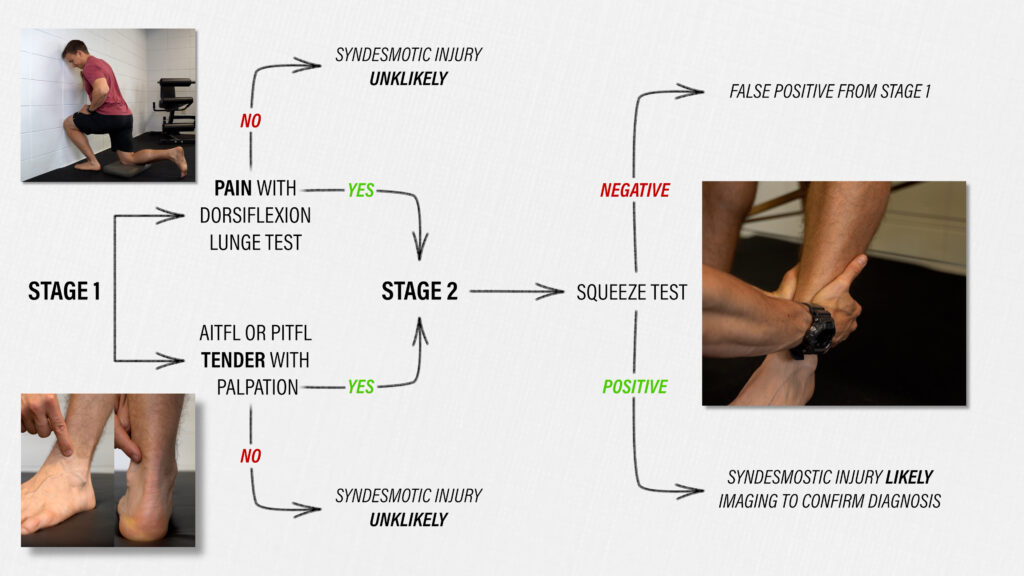

A syndesmotic injury may be suspected based on certain characteristics, such as the mechanism of injury, location of pain, difficulty walking, or the inability to hop on one leg. A recent systematic review with meta-analysis by Netterstrom-Wedin and Bleakley proposed a clinical algorithm for assessing ligamentous injury in non-fractured ankle injuries.

- Stage 1 has two tests: palpation and dorsiflexion lunge. If the AITFL or PITFL are tender to palpation or pain is present with the dorsiflexion lunge, in which you’re comparing ankle dorsiflexion side-to-side in standing or kneeling, move on to stage 2. If both are negative, a syndesmotic injury is unlikely.

- Stage 2 has one procedure: the squeeze test. The intention of the squeeze test is to gap the joint and stress the syndesmotic ligaments without stressing the ligaments normally injured in a lateral ankle sprain. If the squeeze test reproduces symptoms, a syndesmotic injury is suspected and imaging may be warranted to confirm the diagnosis.

This assessment is not all-inclusive. For example, palpation of specific bones may be performed to help rule out a fracture. Additionally, palpation of the deltoid ligament and tenderness up the leg may help identify the extent of the injury.

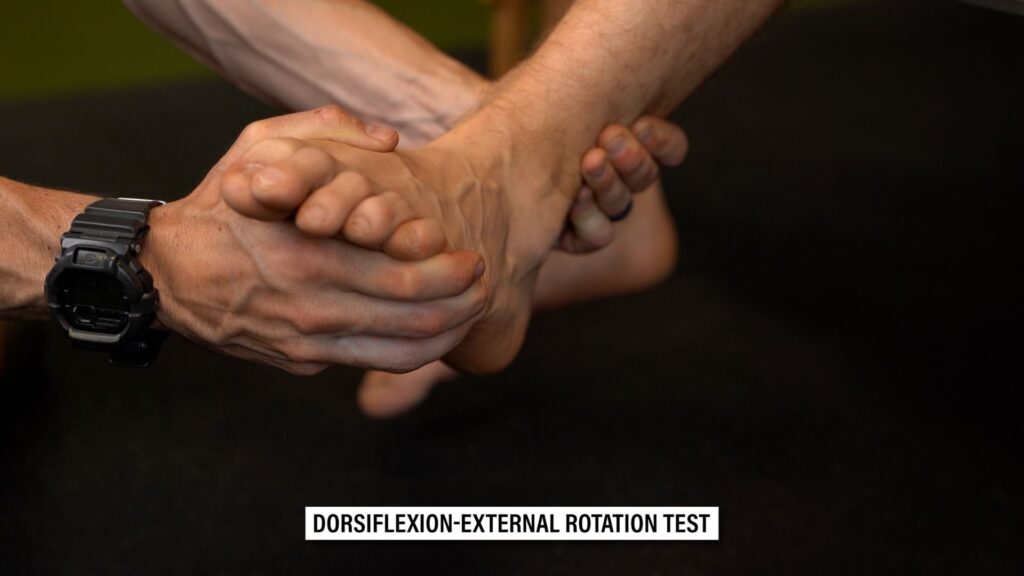

The dorsiflexion-external rotation test, which mimics the mechanism of injury, is also often used. However, imaging and follow-up with a medical doctor are usually required.

High Ankle Sprain Management

Although syndesmotic injuries are less common than lateral ankle sprains, recovery times are generally longer. Initial management is based on the grade of injury.

- Grade 1 injuries, in which the joint is stable, are managed nonoperatively.

- Grade 3 injuries, in which the joint is unstable, are managed with surgery.

Grade 2 injuries can fall into either category, but Lubberts et al concluded that “we are unable to adequately differentiate between stable grade 2 and unstable grade 2 injuries.”

Whether surgery is performed or not, management of syndesmotic injuries will share many similarities along various continuums. The primary differences will be related to the length of precautions, return to sport timelines, etc.

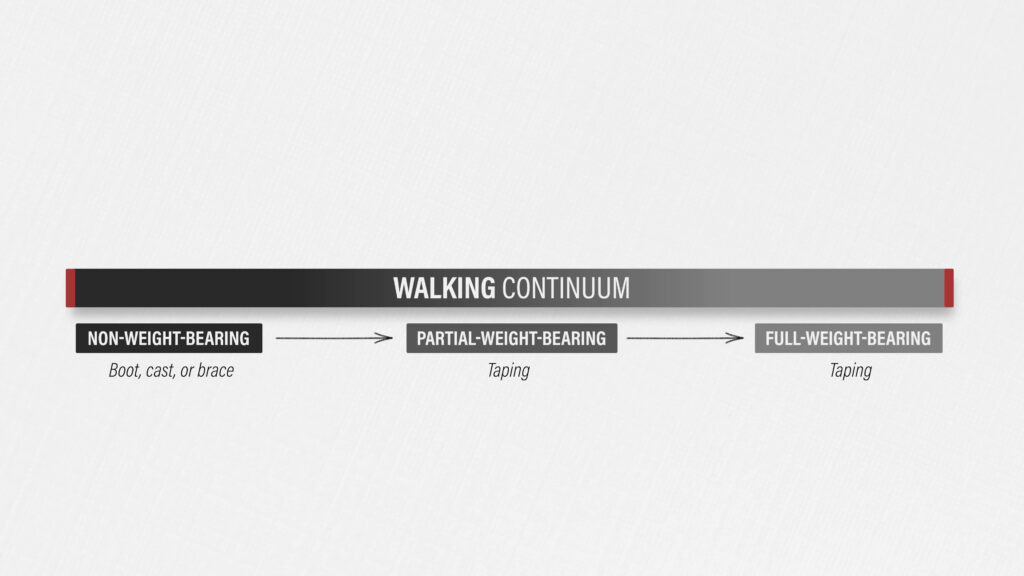

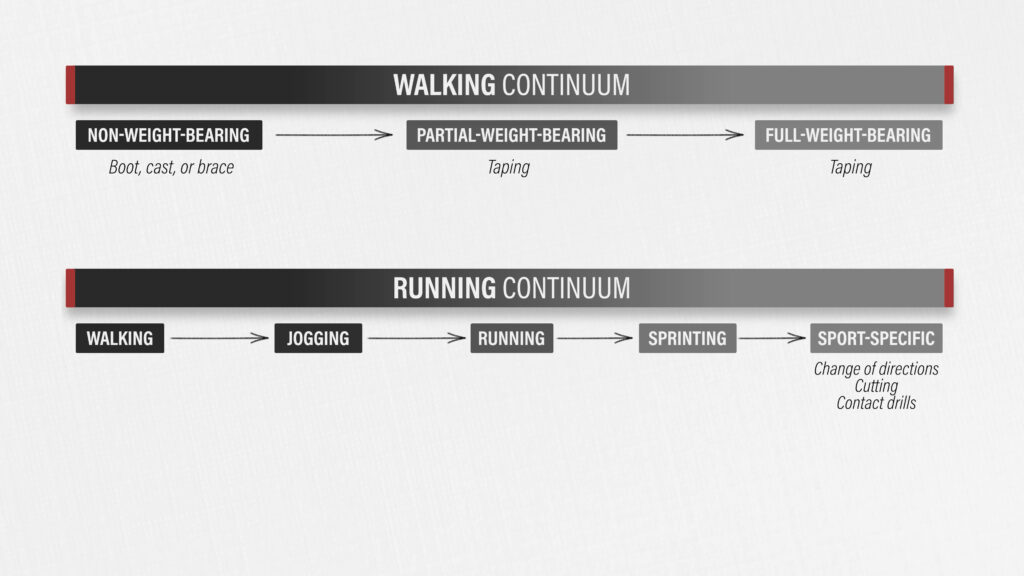

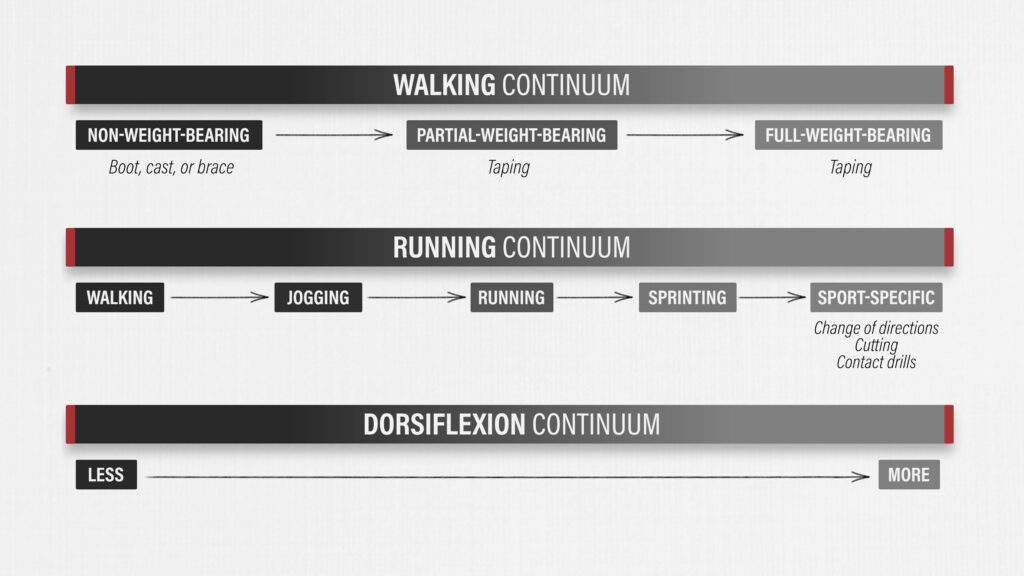

Let’s start with a walking continuum. Almost every case will be managed with a period of immobilization or unloading using a boot, cast, or brace. There may be a transition from non-weight-bearing to partial-weight-weight-bearing to full-weight-bearing over the course of days to weeks. Other exercises may be done outside of the boot in a non-weight-bearing manner to reduce swelling, improve symptoms, and maintain function, but allowing the structures to heal and a gradual return to walking are top priorities. When the initial unloading period is over, taping is typically used to support the joint.

Next is a running continuum. On the far left side is walking and as you move toward the right, you’ll incorporate jogging, running, and sprinting. Based on the mechanism of injury, the far right side will have to include change of direction, cutting, and contact with other players.

Last is a dorsiflexion continuum as it is a major component of the initial injury. Walking and running involve dorsiflexion, but improving the range of motion and tolerance to the position may be enhanced with specific exercises. Here are a few examples:

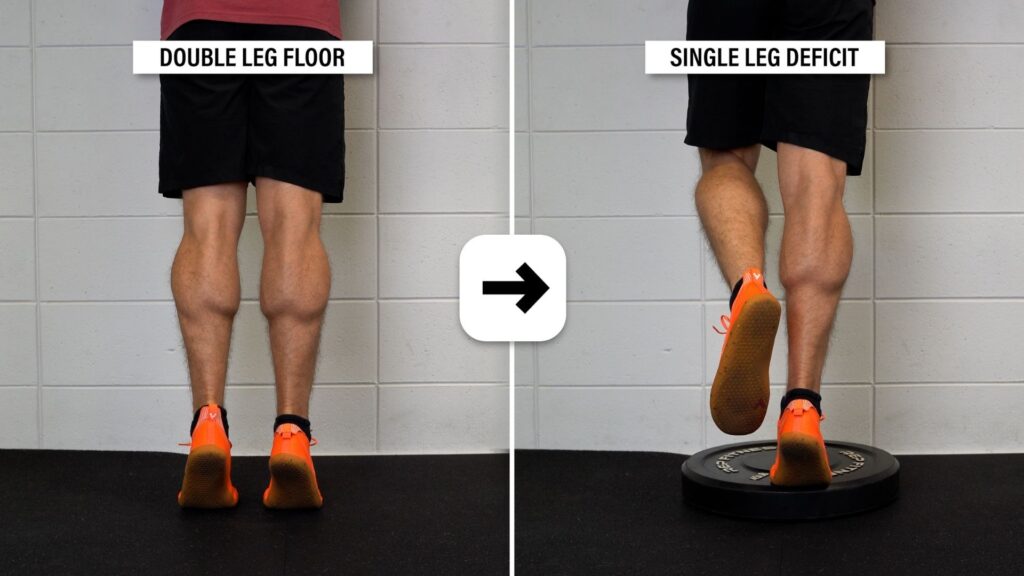

Heel raises can be progressed from 2 legs on flat ground to 1 leg on a step.

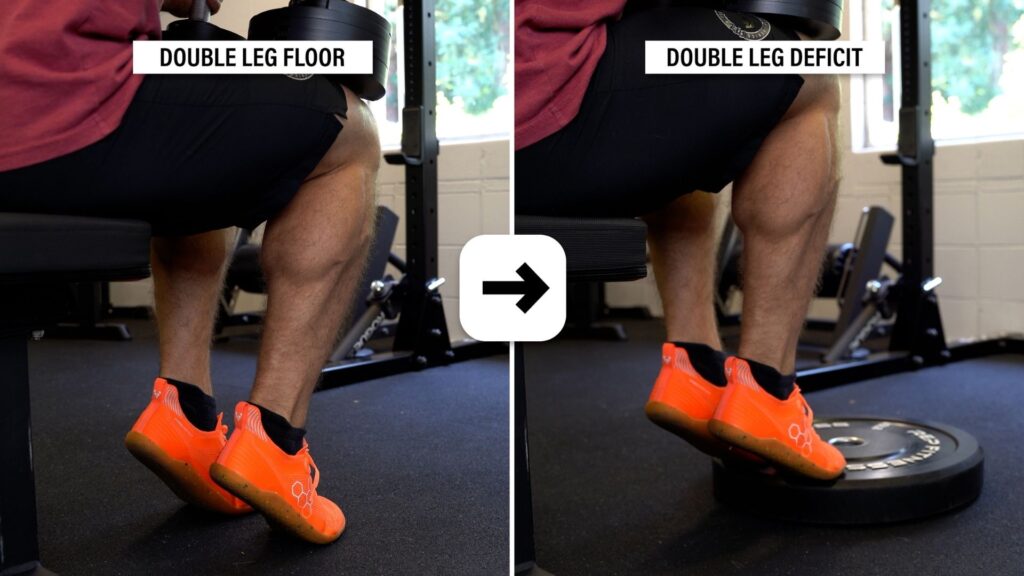

Progressing weighted seated heel raises is another option.

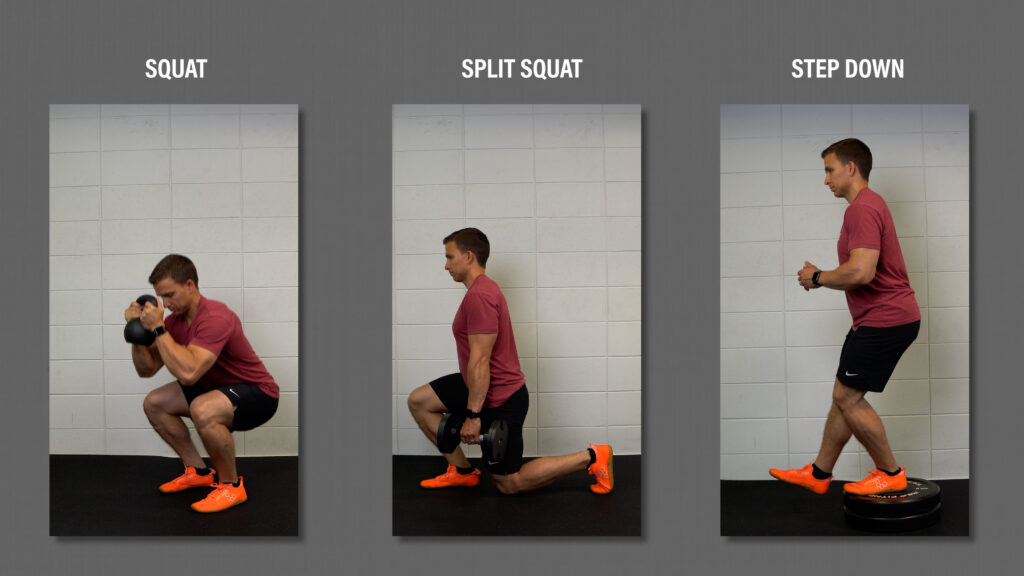

Squatting can start with bodyweight wall sits, box squats, or heel elevated variations to minimize dorsiflexion.

Over time, the shins can be allowed or encouraged to progress forward and weight added with squats, split squats, lunges, step downs, etc.

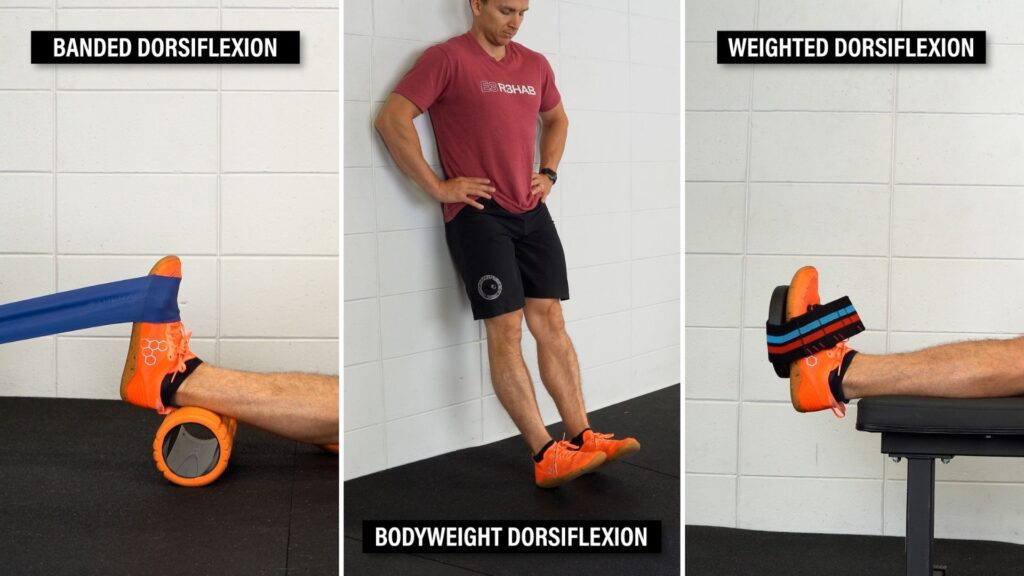

Dorsiflexion strengthening with a band, bodyweight, or weights can complement these other exercises.

Intentionally pushing into pain to improve range of motion or restore function is not recommended.

Return To Sport

There’s no definitive criteria for returning to sport, but here are recommendations from Morgan et al.:

- Minimal to no swelling

- Dorsiflexion range of motion symmetrical and pain-free

- No pain with the dorsiflexion-external rotation test

- Near symmetrical strength and endurance of the ankles, calves, and thighs

- Near symmetrical single leg hop for distance, vertical hop, triple hop, and multiple hop stabilization

- Near symmetrical reaches during the star excursion balance test (SEBT)

- And near symmetrical step balance with running

High Ankle Sprain Summary

In summary, a high ankle sprain, also known as a syndesmotic injury, involves the distal tibiofibular joint and its associated ligaments – the AITFL, PITFL, and interosseous ligament. The injury occurs when your foot is planted, your ankle is dorsiflexed, and your foot is rotating outward relative to your tibia. The majority of injuries involve contact, such as being tackled in football. Due to the high-force mechanism of injury, it’s also possible for disruption of the deltoid ligament and fractures to occur.

A classification system, like the West Point Ankle Grading System, can be used to grade the severity of the injury.

- Grade 1 involves a mild sprain or tear of the AITFL with no instability of the ankle. Non-surgical management is recommended.

- Grade 3 involves complete disruption of the ligaments resulting in instability of the ankle. Surgical management is recommended.

- Grade 2 involves a complete tear of the AITFL and partial tear of the interosseous ligament. Surgical or non-surgical management is dependent on the stability of the joint although stability can be difficult to determine.

Whether surgery is performed or not, management often begins with a period of immobilization or unloading using a boot, cast, or brace. Rehab will consist of a gradual return to walking, running, and end range dorsiflexion range of motion, but it’s important to minimize symptoms and swelling while allowing the joint to heal. Regaining symmetrical range of motion, strength, endurance, and function are key prior to returning to sport.

Syndesmosis injuries can be complex, difficult to rehabilitate, and require longer recovery timelines, so it’s necessary to seek the guidance of healthcare professionals.

Don’t forget to check out our Ankle Resilience Program!

Want to learn more? Check out some of our other similar blogs:

Chronic Ankle Instability, Shin Splints, Heel Raise Benefits

Thanks for reading. Check out the video and please leave any questions or comments below.