This evidence-based blog discusses the ins and out of a total hip replacement from the perspective of a physical therapist and recipient of the procedure 11 years ago at age 19. It is for educational purposes only. It is not meant to diagnose or treat any conditions. Consult with your medical doctor regarding your symptoms, surgery, or rehabilitation.

Looking to improve the strength, range of motion, and control of your hips to enhance your function and performance? Check out our Hip Resilience program!

Total Hip Replacement at Age 19

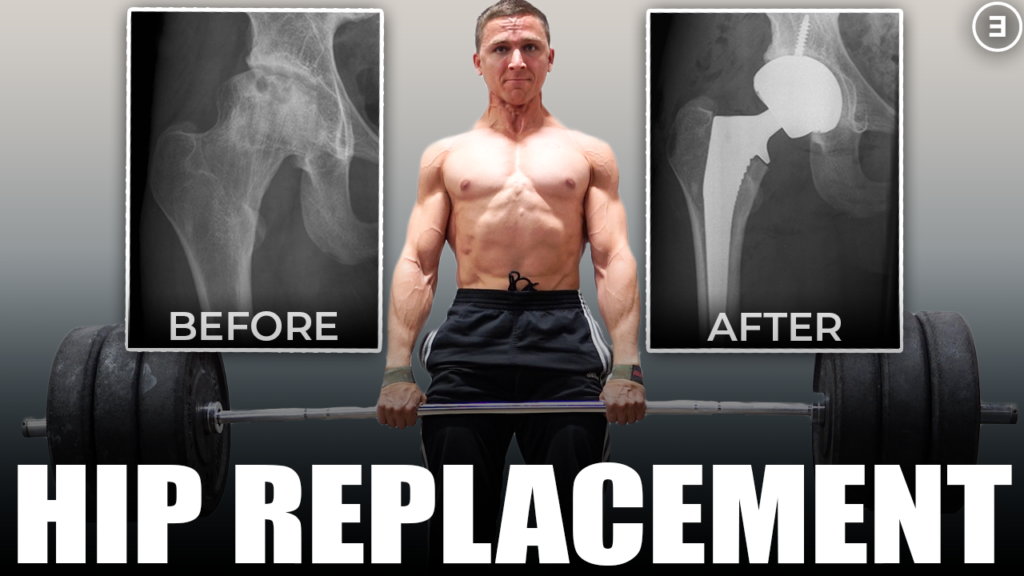

I had my right hip replaced in the summer of 2009 (see “after” picture below). Unlike most individuals who undergo the elective surgery, I was only 19 at the time. I had been suffering from progressively worsening hip pain over the previous two years that made it impossible for me to walk even short distances without a very noticeable limp. A combination of the pain, embarrassment of constantly being questioned by my peers about my awkward gait, and the encouragement from my parents led to the inevitable surgery between my freshman and sophomore years of college.

As we’ll see later, the reason for having my right hip replaced differs significantly than the vast majority of people. I had a condition known as Avascular Necrosis (AVN) which is essentially bone tissue death due to a lack of blood supply (see “before” picture below) [1]. AVN may be caused by trauma, excessive alcohol consumption, or other conditions, but it is most commonly seen in younger, active populations secondary to corticosteroid use [1,2]. Cases of AVN have been reported from both short and long-term usage of corticosteroids across various applications [2]. However, the exact mechanism behind this condition is unknown and it is likely to be multifactorial in nature [1]. Unfortunately, a high oral dosage of corticosteroids for 3 years to combat a separate medical issue likely led to my development of AVN.

Other than what my surgeon told me, I didn’t know much about the operation. However, 11 years have passed (I’m 30 at the time of publication) and I’m now a Doctor of Physical Therapy. I want to provide the research on the topic while presenting my unique perspective on the various facets of rehabilitation and decision-making.

Brief Background

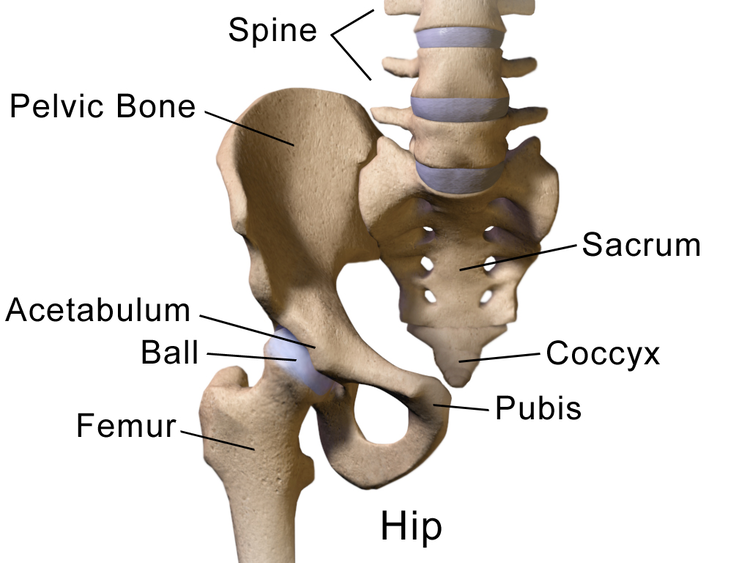

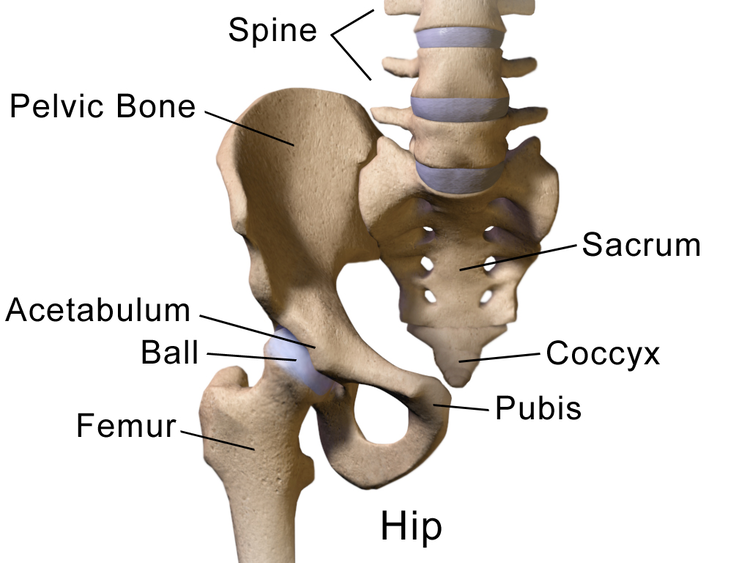

In order to understand the surgical procedure, it’s important to briefly review the anatomy of the region. The femoroacetabular joint, commonly referred to as the hip, is the articulation between the head of the femur (thigh bone) and acetabulum (part of the pelvis). It is an extremely stable ball-and-socket joint that allows for movement in all planes of motion.

Touted as “the operation of the century”, the development of the first hip implant began with Themistocles Glück in 1891 [3]. However, John Charnley is widely recognized as the father of modern total hip replacements for his extensive work on developing and refining the successful procedure in the second half of the 20th century.

Since that time, the rapid growth of this procedure has seen it performed millions of times around the world. In the United States alone, the number of total hip replacements increased from 158,856 in 2000 to 370,770 in 2014 (132% change!) [4]. By 2030, it is projected that this number will increase to 635,000 (71% growth) [4].

Who gets a Total Hip Replacement?

Although the data slightly varies by country, the average age for individuals undergoing an elective primary total hip replacement in the United States is 65.6 [5]. An elective operation is one that is scheduled in advance rather than requiring it out of necessity for something like an unexpected femoral neck fracture. The word “primary” refers to a first time surgery as opposed to having a revision which will be discussed later. The majority of people under the age of 50 who undergo the procedure electively are male (55.7%); however, females make up the the majority overall (59%) and each increase in decade of life shifts this statistic further in that direction [5,6].

The primary indication for a total hip replacement is osteoarthritis (OA) as is seen in 90% of cases [6,7]. After the knee and hand, the hip is the third most common joint affected by this condition and its prevalence continues to increase secondary to longer lifespans and greater rates of obesity [8].

According to Hunter et al., “age is one of the most evident risk factors for OA” as a “result of cumulative exposure to various risk factors and biological age-related changes in the joint structures”. However, contrary to popular belief, OA is not simply caused by “wear-and-tear”. Instead, it is a multifactorial process involving mechanical, inflammatory, and metabolic factors, with genetics potentially accounting for up to 40-80% of the contribution in the hip [8].

Common clinical findings of hip OA include morning stiffness, reduced range of motion, crepitus (joint noise), muscle weakness, fatigue, loss of function, and pain [8]. While it may seem surprising, the standard for confirming osteoarthritis is a clinical diagnosis based on patient-reported symptoms and the healthcare practitioner’s physical examination. Therefore, plain radiographs may not always be warranted. Additionally, x-rays and MRIs only show moderate associations between structural changes seen on imaging and pain [8]. It is possible to have significant changes on imaging with little pain and little change on imaging with significant pain, which makes it vital to assess the person as a whole rather than just their respective joint.

Since symptoms associated with osteoarthritis are variable and may wax and wane over time, it is recommended that the first line of treatment includes appropriately dosed exercise, weight loss if overweight or obese, education, and assistive devices as needed [8]. In fact, Hunter and colleagues only suggest referral to a surgeon if patients have been unsuccessful with conservative management after a period of 6 months and quality of life is significantly reduced [8].

According to a review of the literature by Gademan et al., the indication criteria for determining who receives a total hip replacement is largely based on expert opinion as evidence is limited and poor [7]. Fortunately there is some consensus in that “most indication criteria consisted of the following three domains: pain, function, and radiological changes, with the prerequisite that pain could not be controlled by conservative therapy” [7]. Specific cut-off values were not reported for these measures so it is likely that these domains are considered on a case by case basis.

Determining who is appropriate for surgery may be guided by factors such as age, surgical risk, previous nonsurgical treatments, pain, and functional limitations. However, uncertainty exists in up to 42% of cases based on algorithms accounting for these variables [7]. Worse outcomes may also exist for patients who are depressed, obese, demonstrate minimal radiographic changes, or report minimal pain [8].

According to Sansom and colleagues, individuals who eventually opt for a total hip replacement get to that destination by one of two routes: they wait until symptoms are unbearable (“holding off”) or they seek care preemptively (“before symptoms get worse”) [9]. The majority of people try to hold old off until the consultation is seen as urgent secondary to a rapid deterioration in function. The others do it while they are young and healthy so they can recover better. Regardless, there is often anxiety, concern, and disappointment associated with the process, especially if there is a mismatch between patient and provider beliefs. An example of this would be if the patient believes they are indicated for the surgery, but the surgeon disagrees because the pain isn’t severe enough or there is a misdiagnosis [9].

Hopefully this section highlights the complexity of osteoarthritis and the difficult decision-making process associated with determining who is appropriate for a total hip replacement. The surgery is often viewed through a biomedical lens – degeneration leads to pain secondary to wear and tear which needs to be fixed through surgery. However, it is not a simple linear process and all aspects of a person’s life must be considered by approaching the issue using a biopsychosocial framework.

What is a Total Hip Replacement?

While you don’t need to know all of the intricacies of the surgical procedure, I think it can be helpful to have a basic understanding. Please be advised that the following information should not sway you to choose one type of implant over another as your surgeon will use the best available option for you at that time.

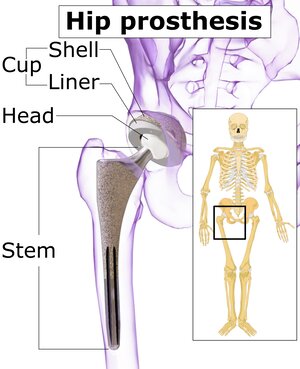

Also known as a hip implant, hip prosthesis, or total hip athroplasty, a total hip replacement refers to the removal and replacement of the native joint using modern technology. For the most part, a normal, healthy hip will have a “ball” (top of the femur) that is spherical in nature and sits nicely within its “socket” (acetabulum) which can be seen in the “normal” image below. However, in quite extreme cases such as my “abnormal” x-ray shown below, the integrity of the joint is lost and a replacement is necessary to restore function.

But what does it actually mean to have your hip replaced? Orient yourself to the two figures below. In both images, we are looking at a right hip from a frontal view. In the normal hip, we can once again visualize the head of the femur (ball) joining with the acetabulum (socket). In the picture labeled “hip prosthesis”, we can appreciate that the head of the femur, the neck of the femur, and the inner portion of the femur have been removed to make way for what’s known as the femoral component, or the head and stem. On the other hand, the socket has been replaced with the acetabular component, or the shell and liner. Let’s explore a little further.

We have four components right now: stem, head, liner, and shell. The stem is metal and placed within the hollowed out femur, while the head can be metal or ceramic. The liner may be metal, ceramic, or a very durable type of polyethylene (plastic). Finally, the shell is either metal or nonexistent because the entire cup is made of one material such as polyethylene (known as a monobloc cup).

The components of a total hip replacement can be secured using one of four methods:

- Cemented – bone cement is used to secure the femoral and acetabular components.

- Uncemented – no bone cement is used. Instead, the procedure relies on press fit and osseous integration (bone grows into and around the implant). The cup may be further stabilized with a screw.

- Hybrid – Only the femoral component is cemented.

- Reverse Hybrid – Only the acetabular component is cemented.

The trends for hip replacements vary around the world. Based on data from England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Isle of Man from 2003 to 2018, we can appreciate the most commonly used components in this region [6]. The femoral head component is listed first, followed by the shell and liner, or cup.

- Metal-on-polyethylene cemented monobloc cups n=327,147

- Metal-on-polyethylene uncemented metal shells with polyethylene liners n=297,291

- Metal-on-metal uncemented metal cups or metal shells with metal liners n=31,435

- Ceramic-on-polyethylene cemented monobloc cups n=50,738

- Ceramic-on-polyethylene uncemented metal shells with polyethylene liners n=155,790

- Ceramic-on-ceramic uncemented metal shells with ceramic liners n=150,908

From this data we can see that cemented metal-on-polyethylene was the most commonly used prosthesis during this time frame (28.5%). Overall, usage of ceramic-on-polyethylene has been increasing, ceramic-on-ceramic decreasing, and metal-on-metal has drastically reduced since 2011 secondary to high failure rates and concerns with blood metal ion levels [6]. Cemented fixation was most commonly utilized between 2003 and 2007, uncemented between 2008 and 2016, and now hybrid in 2018 (31.2% vs 27.3% for cemented) [6].

Trends in the United States are slightly different. The vast majority of elective primary total hip replacements use cementless femoral component fixation (94.3%) and survivorship is higher in individuals >65 compared to its cemented counterpart [5]. However, cemented femoral component fixation does become more common in the elderly as it is used in 13.1% of individuals between 80-89 and 31.3% of individuals 90 or older [5]. Cross-linked polyethylene is the customary acetabular component, while rates of ceramic femoral head usage has been increasing and cobalt chromium (metal) decreasing [5]. Ceramic is significantly more popular in individuals 69 or younger, but metal is used more often above this age range [5].

There are other considerations when selecting the appropriate prosthesis such as femoral head size, but I think that’s less important to explore at this time.

As I mentioned earlier, you should likely just accept whatever implant your medical doctor recommends as they know far more about the technology than you or me. I have an uncemented metal-on-metal hip replacement with an added screw for fixation of the acetabular component. M-o-M was extremely popular at the time of my surgery and it was meant to improve my available range of motion while minimizing the long-term wear of the artificial joint. Two years later my particular implant was recalled and my surgeon and hospital system had to make a disclaimer video on YouTube (great!). There’s nothing I can do, though. Plus, I haven’t had any significant issues and I’m still going strong 11 years later so it’s not something that causes me stress.

If you’d like a better visual of the surgery, I have embedded a video below.

What Are The Surgical Options?

Named for their points of entry, the three most popular techniques used for a total hip replacement are the direct anterior, direct lateral, and posterior approach. The direct anterior approach has made a resurgence in recent years, but it’s also been around for more than 100 years. Similar to the previous section, I would choose my surgeon based on their overall track record rather than what approach they are trained to perform.

Although there are some inconsistencies in the research, the direct anterior approach seems to be associated with a shorter length of stay in the hospital, reduced pain in the short-term, and improved function in the short and medium-term compared to the direct lateral or posterior approaches [10-13]. So why doesn’t every surgeon simply pick this approach?

Well, there can be a steep learning curve and other complications do arise. In a retrospective cohort study with at least 2 year follow-up by Aggarwal et al. in 2019, the direct anterior approach had the highest incidence of complications compared to the other approaches examined. These complications included superficial infection, deep infection, prolonged wound drainage, periprosthetic fracture, dislocation, aseptic loosening, and other issues. The direct anterior approach ranked highest for all of these measures. However, the percentage of complications was only 8.5% (113/1329) compared to 5.85% (97/1657) in the posterior approach and 6.11% (24/393) in the direct lateral group. Dislocations occurred in 1.28% of the anterior group and .84% in the posterior group. The direct anterior approach also led to the most re-operations at 4.7% compared to 3.1% and 2.8% in the posterior and direct lateral groups respectively [13].

A separate retrospective study by Fleischman and colleagues looked at 16,186 total hip replacement procedures between January 2010 and June 2016. Of the surgeries completed at this single institution, 5,465 cases were performed using the direct anterior approach (33.8%), 8,561 using the direct lateral approach (52.9%), and 2,160 using a posterolateral approach (13.3%) based on surgeon preference. All implants were cementless and only hip precautions were given to the posterolateral group (which we’ll discuss later). The most common complications included instability/dislocation, periprosthetic fracture, and aseptic loosening. The incidence of all mechanical complications was 2.57% in the direct anterior group, 2.13% in the posterolateral group, and 1.09% in the direct lateral group at the 2 year mark. Overall, risk of instability/dislocation was highest for the posterolateral group at 1.74% compared to .74% and .17% in the direct anterior and direct lateral groups despite the hip precautions. The risk of having to return to waiting room at 2 years was 1.77% for the direct anterior approach, 1.2% for the posterolateral approach, and .81% for the direct lateral approach [14].

That changes things significantly then, right? Not really. The previous study demonstrated the least amount of complications using the direct lateral approach, but this might be influenced by the fact that the majority of surgeons chose this approach (52.9%) so the institution as a whole may be more familiar with this procedure. You might be wondering why the percentage of complications is so much lower in the second retrospective study. Well, Fleischman et al. only looked at mechanical complications compared to the Aggarwal paper that also looked at things like superficial and deep infections. Finally, the absolute risk increase for the direct anterior approach is only around .6% which isn’t all that significant on an individual level [14].

Pick your surgeon based on their track record and your rapport with them. Each approach will have its pros and cons. The anterior approach may allow you to recover quicker because it spares the glutes and deep external rotators of the hip, but there might be a higher trend for complications. However, what we do see from the Fleischman paper is that surgeons who performed a higher volume of total high replacements had a reduction in mechanical complications by 23.9% for each additional 10 cases per month [14].

My surgeon utilized a posterolateral approach (direct anterior was much less common in 2009) so I have a nice scar on the side of my glutes. I’d venture to say my hip abduction and external rotation is still weaker on that side with slightly noticeable atrophy, but it doesn’t impact my function in any meaningful way. When I have to inevitably get the other side replaced (less severe AVN) or need to have this one revised, I’ll pick the surgeon with the best outcomes in my area.

Overall, every approach is extremely successful.

What Can You Expect After Surgery?

From 2012 to 2018, the average length of stay in the hospital after the operation has reduced from 2.6 days to 1.9 days [5]. That means you can expect to be back on your feet in some capacity rather quickly. In fact, several studies have shown that it is possible for individuals to be discharged home on the same day of the procedure [15-17].

In order to meet this criteria, patients had to be able to use the restroom independently, navigate stairs, ambulate 80-100 feet, demonstrate normal urinary function, feel confident in doing so, and have assistance at home, just to name a few [15,16]. Physical therapy was initiated within 1.5-4 hours of the surgery. Talk about resiliency of the human body!

Common reasons individuals were not discharged the same day included nausea, dizziness, pain, patient preference, and ambulatory difficulty, among other reasons [15,16]. Younger individuals and those with less comorbidities were more likely to go home on the same day while major comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and benign prostatic hypertrophy increased risk for overnight observation [16,17]. Certain criteria excluded patients from being represented in the studies or acted as contraindications including age >75, BMI >40, chronic opioid use, no assistance at home, congestive heart failure, severe renal disease, and others. [16,17].

Much of the research examining same-day discharge is relatively new so it may not be a realistic expectation that your institution will recommend or allow it. However, it should highlight how well people recover from the procedure. You can expect to be walking and accomplishing many basic activities in a relatively short amount of time. If you’re fit and able, you may be provided axillary crutches for assistance. If you’re older or less fit, a walker might be more suitable.

I was walking and navigating stairs on the same day of my operation with the help of a wonderful physical therapist and a pair of crutches. I was determined to be discharged on the same day (I’m not sure if it was even an option to be honest), but urinary retention hindered any chance of that option (hooray for catheters!).

What are the Short-Term Outcomes?

As I’ve already mentioned, total hip arthroplasty has been touted as the operation of the century. And for good reason! It’s a testament to human ingenuity as it allows many individuals with severe pain and impaired function to eventually lead very active and meaningful lives. However, like with any surgery, absolute certainty of a preferred outcome does not exist.

One of the primary concerns associated with a total hip replacement is the need for a revision. A revision is a replacement of the implant secondary to failure that can happen early in the life of the prosthesis or after many years.

The most common causes of early hip revision are infection and inflammatory factors (23%), instability (19.7%), and fracture or fracture related sequelae (16.6%) [5]. Early infection generally occurs within 4-8 weeks and has a significant impact on function, quality of life, and mortality risk [18]. According to Monsef and colleagues, some risk factors include BMI >30, prolonged hospital stay, various combordities, age, malnutrition, prolonged operative time (150 minutes), blood transfusion, and a bilateral surgery [18].

The majority of dislocations (50-70%) occur within 3-6 months of the initial operation, but are most common within 6 weeks [18]. Unfortunately, 1/3 of those tend to recur. Taken from Monsef et al., the list of possible risk factors is quite long: age >70, combordities, female sex, ligamentous laxity, abductor insufficiency, inability to follow hip precautions due to neuromuscular disorders or cognitive impairment (more on this later), and a variety of surgical factors. Prosthesis design also plays a role [18].

Most revisions happen within the first three months of the operation (55.4%) and the prevalence increases with each increasing decade of life after the age of 69. For example, early revision is seen in 1.9% of patients >90 compared to 1.24% of individuals between the ages of 50 and 69 [5]. As you can see, only a very low percentage of individuals require an early revision.

Long-Term Outcomes: Answering 2 Key Questions

Will I be Pain Free?

When it comes to working with an individual for rehabilitation, regardless of the injury or reason, one of the most important things that I can do as a physical therapist is set realistic expectations. While becoming pain free after a total hip replacement would be ideal, it might not be completely realistic. But it’s probably also not necessary.

What activities were limited prior to the surgery? Let’s focus on functional goals while using pain as a guide. Can I guarantee pain free? No, but I can likely promise a significant improvement in function and quality of life.

Based on a patient reported outcome measure known as the HOOS, JR. (hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score), 93% of patients in the American Joint Replacement Registry reported a meaningful improvement after a total hip replacement [5]. However, in a different follow-up study by Beswick et. al in 2012, it was estimated that 7-23% of individuals have unfavorable outcomes as indicated by moderate-to-severe pain after surgery, or failure to relieve pre-surgical pain altogether [19].

Am I pain free? With most day-to-day activities, I actually am. I don’t have pain with walking, squatting to a chair, toilet, or couch, or while performing my activities of daily living (unless the hip is already flared up).

Are all activities pain free? No, but most things are tolerable. If I want to sit for extended periods of time, run, lift weights a particular way, play sports, hike, etc., I have some level of pain. We’ll touch on this more in a later section, but I’ve had 11 years to adapt to this artificial joint. I understand that it’s better than my hip with AVN, but it’s never going to function as well as my native hip when it was healthy. I have had to make sacrifices and I will continue to make sacrifices to ensure the longevity of my implant while maintaining a quality of life that I deem acceptable.

You have to understand that surgery should never be seen as a quick fix. It’s not a passive process. You have to put in work before and after the operation. You have to try to prioritize your health by managing nutrition, stress, sleep, fitness, etc. Surgery “fixed” my damaged hip, but that was just the start of my recovery.

How Long Will the Total Hip Replacement Last?

As we explored in a previous section, older individuals are more likely to require an early revision, and the risk of mechanical complication increases by 12.6% with each increasing decade of life [14]. Intuitively, this makes sense. They likely have more comorbidities, a lower functional capacity, poorer bone health, slower rates of healing, etc. However, the risk of revision across the life of an individual actually increases with decreasing age, especially for men and those under 60 [20].

Once again, this makes intuitive sense. The longer you live with the implant, the more likely you’ll need a revision at some point in your life. The National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and the Isle of Man showed that men and women over the age of 75 have less than a 5% chance of requiring a revision [6]. Similarly, Bayliss et al. demonstrated that the risk for individuals over the age of 70 requiring a revision was only 5% [20]. Therefore, if you’re 70 years of age or older at the time of surgery, you can expect your total hip replacement to last your entire life. In the same study, it was reported that the lifetime risk of revision for men in their early 50’s who have the operation is as high as 35%. For women, the risk in this age range was about 20% [20].

Long-term implant survival rates often vary by registry and study, but Evans et al. 2019 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up in The Lancet and found that the percentage of total hip replacements that lasted 15, 20, and 25 years was 89.4%, 70.2%, and 57.9% respectively [21]. The National Joint Registry mentioned above showed that “revision rates due to aseptic loosening and pain increased with time from surgery, whereas the rates due to subluxation/dislocation, infection, periprosthetic fracture, and malalignment were all higher in the first year and then fell” [6]. In the medium and long-term, aseptic loosening is the most common mechanism of failure [18].

Aseptic loosening is a multifactorial phenonenom that refers to loosening, or failure of the connection between the implant and bone, that isn’t due to infection. Bone resorption, or breakdown (osteolysis), is often driven by wear debris (think of particles released around the joint that cause various cellular responses). Aseptic loosening can be a symptomatic or asymptomatic occurrence so it’s important to follow up with your surgeon based on their recommendations [18].

In the American Joint Replacement Registry, current smokers were 42% more likely to need a revision compared to individuals who had never smoked [5]. Additionally, “the earlier the primary hip replacement is revised, the higher the risk of a second revision” [6].

Much of this sounds like bad news, but I’m just trying to provide the objective data. It is a quite successful surgery and we’ve seen 3 and 5 year revision rates decrease over the last 10 years [6]. Long-term outcomes have also improved since the decrease of metal-on-metal hip replacements.

As I discussed in the last section and will discuss in the next sections, surgical success (however we choose to define that) cannot be 100% guaranteed, but we can likely increase our likelihood by taking the appropriate precautions. Behavior change is difficult, but quitting smoking, taking up a healthy lifestyle, collaborating with your medical team (doctor and physical therapist) before and after the operation will likely lead to a better overall experience. If you’re already doing these things, you’re setting yourself up for success!

Reminder – it’s a very successful surgery!

Hip Precautions

I’d like to briefly touch on hip precautions since it’s often a controversial topic and the last two sections on rehabilitation and return to sport are largely anecdotal in nature secondary to a lack of high quality evidence. Historically, hip precautions have been given after the procedure as a means to reduce the risk of dislocation. For example, after my total hip replacement, I was told not to flex my hip above 90 degrees, adduct my hip across midline, or internally rotate my leg (for 4 weeks I think).

Not flexing my hip above 90 degrees meant that I had to use a raised toilet seat and a grabber to help me pick up things from the floor. Not adducting my hip across midline meant that I was unable to cross my legs (not something I do anyway) or sleep on my side (I wasn’t given a pillow or instructions from what I recall). I like to sleep on my side so it was not easy getting a restful night of sleep. Combined, these restrictions severely limited my day-to-day life, but I stuck to them until I was advised otherwise.

The prescription of hip precautions after a total hip replacement are not universally uniform. In a survey of surgeons who are members of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (AAHKS) or Canadian Arthroplasty Society (CAS), 44% of respondents reported giving hip precautions to all patients while 33% gave no hip precautions. Precautions also seem to vary by procedure as it is more common to give precautions to individuals undergoing a posterior approach (63.2%) compared to those undergoing an anterior approach (16.8%). Precautions were most commonly provided for 5-6 weeks (49.2%), followed by more than 8 weeks (27.1%). More experienced surgeons were more likely to give precautions than less experienced surgeons, but less experienced surgeons gave precautions for a longer duration postoperatively [22].

In a retrospective study by Gromov and colleagues, they found that the removal of hip precautions did not increase the risk of early dislocation (within 90 days) for patients who received a total hip replacement using a posterolateral approach [23]. Similarly, a systematic review by van der Weegen et al. in 2016 showed that dislocation rates were no worse for anterolateral or posterior approaches for patients with unrestricted or less restricted protocols. Patients were also able to resume activities quicker and reported higher satisfaction with the pace of their recovery [24].

Clearly, there’s some discrepancy here. Does this data mean that we should simply throw out all precautions? It’s a difficult situation. Although the numbers suggest that it might be safe to do so, physical therapists and surgeons are likely concerned with litigations. It comes with the territory. What if a patient had a dislocation for a completely unrelated reason, but decided it was because they weren’t given any precautions? Other aspects also influence dislocation rates such as surgical experience, the patient’s BMI and age, and various intraoperative factors [25].

What’s my advice? Discuss it with your surgeon beforehand! Tell them your concerns. Show them the cited papers if you want. Understand their reasoning and perhaps you can come to an agreement. If you’re otherwise healthy, hopefully there’s no reason you can’t begin resuming normal activities sooner rather than later.

Rehabilitation Preamble

Time for the good stuff! The purpose of these sections is not to outline a step-by-step postoperative protocol as there are dozens of these that can be quickly found with a simple Google search. Instead, I want to present the principles of successful rehabilitation so you can adapt the process to meet your individual needs. Everything discussed should be taken into consideration prior to the surgery as well since prehabilitation has been demonstrated to improve pain and function while decreasing length of stay in the hospital following the operation [26].

Let’s start by addressing the elephant in the room – do you actually need supervised physical therapy after your total hip replacement? The research would suggest that perhaps you do not [27,28]. Before I get struck down by my fellow physical therapists, please let me explain.

Does everyone (key word here!) need supervised physical therapy after total hip arthroplasty? Probably not. Austin et al. 2017 and Coulter et al. 2017 have shown us that people can do just as well by performing exercises at home compared to individuals attending formal rehabilitation [27,28]. This is a good thing! A really good thing! It’s further evidence that this surgery is phenomenal. Also, it’s a great way for some people to save time and money who don’t have the ability to spare either.

There are several caveats, though! For example, the participants in the study by Austin and colleagues were relatively young (average age was 61.7) with no postoperative complications, received physical therapy in the hospital, and followed up with their surgeon 2 weeks postoperatively. They weren’t left to fend for themselves. Additionally, ten patients who were performing exercise at home in an unsupervised manner ended up switching to formal physical therapy after 2 weeks because they were not meeting their goals. These patients tended to be older with worse preoperative function [27].

Another important component of both studies is that they used the Harris Hip Score (HHS) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) to measure success [27,28]. These patient reported outcomes measures are valid and reliable questionnaires used to assess function and symptoms in individuals with osteoarthritis and total hip replacements, but relatively young, healthy, and active adults will likely hit a ceiling.

So who would likely be a good candidate for unsupervised postoperative rehabilitation? Individuals who:

- are motivated and healthy

- demonstrate good pre and postoperative function

- are given clear instructions before and after the surgery

- have assistance at home

- follow-up with their surgeon as needed

- don’t have goals to return to high level sports or activities

The last point is extremely important to me. My first bout of rehabilitation was an absolute joke which is probably why I only went for 1-2 visits. However, my second round of physical therapy at Arizona State University was a monumentally different experience. The actual physical therapist did some passive stretching with me which didn’t accomplish much, but his assistant was a strength and conditioning coach with a Master’s in Exercise Science. From months 4 to 6, she kicked my butt. She had me doing high level single leg plyometric work (along with strength training) in a controlled manner that boosted my physical function, confidence, and psychological resilience. The WOMAC and HHS wouldn’t capture that. I was eager to get back to some semblance of normal for a 19-year-old and she helped get me there.

Side note: months 2 and 3 just consisted of a lot of cycling to and from school, walking, and basic exercises.

Rehabilitation Guidelines

We’re going to make two assumptions here: no hip precautions and no complications. If you have hip precautions, these exercises can be modified to suit those restrictions but you’d need to talk to your surgeon. Also, these exercises cannot account for every comorbidity, health condition, or issue that may or may not be associated with a total hip replacement, so exercise prescription should always be tailored to the individual.

Before discussing the exercises, it’s important to set general guidelines. A total hip replacement is an injury. Every surgery is in its own right. The joint is strong and stable, but it needs to be given time to heal. You need to respect that throughout the process. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle will help create the appropriate environment for healing, but there is nothing that can be done to magically accelerate the process. Is doing too much going to damage the implant in any significant way? Unless you did something way out of context, it’s very unlikely. However, it’s still helpful to minimize unnecessary flare-ups. “No pain, no gain” isn’t useful here.

Let’s elaborate on this last point a bit more. Pain does not mean you are damaging your joint, but it’s also not an invitation to throw caution to the wind. You are surely going to have ups and downs throughout the rehabilitative process, but monitoring your pain and function can help you track progress.

Will you have discomfort with various movements, exercises, positions, and postures? Surely. It’s completely normal. How much is too much? Some of that is up to you. Pain needs to be tolerable during exercise without lingering symptoms that impact your ability to function or sleep. You shouldn’t be waking up with worse pain the next day and you shouldn’t have to pop back a handful of pills just to get through a few movements. If any of these things do happen though, it’s fine! It’s just an indication that you did a little too much, too soon! Scale back and find a more manageable starting point.

Some individuals like very specific guidelines so here are a few that might be helpful for you:

- If you measure pain on a scale from 0 to 10 with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain possible, don’t let pain increase by more than 2 points. This does not mean it can’t go above a 2/10. It means that if your starting point is 1/10 when you begin the exercise, keep the pain at 3/10 or less.

- Discomfort might limit your ability to fall asleep and stay asleep. However, your exercises shouldn’t increase that baseline level of discomfort at night so it’s harder to fall asleep or stay asleep.

- Pain from your exercise routine shouldn’t make your daily activities more challenging. For example, if you normally have a 2/10 pain with your nightly 20 minute walk with your significant other, the exercises shouldn’t make your pain spike to a 5/10 that now limits you to only 10 minutes.

- Pain from exercises shouldn’t impact your baseline morning symptoms. For example, if you normally have a 1/10 pain with dressing in the morning, you should not have lingering symptoms from the day before that now feel like a 4/10.

- If any of these things happen, do not panic! You likely did not injure your joint. Think about what you did the day before and consider if you just exceeded your current capacity.

Total Hip Replacement Rehabilitation

When it comes to rehabilitation, there are two key components that stand out above the rest to me: walking and squatting. If you can create a solid plan to increase your total tolerable walking distance each week and squatting capabilities, you’re going to do really well. Third on my list would be ascending and descending stairs. Finally, we’ll end by discussing a comprehensive exercise routine for individuals who want more, or plan to return to higher level activities.

Walking is the cream of the crop here. Whether you’re using an assistive device or not, you need to be practicing this daily. You don’t need to be thinking about muscle activation or joint range of motion – you just need to walk. At the very least, work your way up to 1 mile per day, but 2-3 miles is even better. Break these walks up into as many bouts as you need throughout the day as long as you’re observing the guidelines mentioned above. It sounds way too simple, but this is one of the best things you can do for yourself after a total hip replacement. Get walking!

Daily life requires a lot of squatting! You squat to and from the toilet, the couch, and the dining room chair. You even squat to pick things up. You need to become a proficient squatter. This doesn’t mean you need a barbell on your back or fancy equipment. I’m not giving a timeline here as it’s going to vary for each person (and I’m assuming no precautions!). Here’s a sample progression (click to view exercises):

- Box Squat (or chair, couch, bed, etc.)

- Start with an elevated surface that you can manage comfortably. Think about tapping the box/chair with your butt as you sit as if you do not want to crush an egg (forces you to control the motion). If you cannot do that, raise the height of the surface, use arms for assistance, or use slight momentum to start.

- Work toward performing the box squat without any of the aids mentioned above for 3-4 sets of 15-20 repetitions with no increase in pain before progressing to the next step.

- Split Squat with Reduced ROM

- I like the split squat for various reasons including the ability to modify depth/difficulty, requires asymmetrical loading, and allows you to change hip flexion range of motion to match your comfort. My hip doesn’t enjoy deep hip flexion so I’m able to load split squats more than traditional squats with less discomfort (by staying more upright).

- Stack as many pillows/pads as needed to make the movement manageable for you. Slowly increase the depth of the movement until you can perform 3-4 sets of 15-20 repetitions with only 1 pad.

- Split Squat

- From here, you can just progress to tapping your knee to the floor. Similar to the box squat, pretend you’re tapping an egg that you do not want to crush. Control the movement. Aim for 3-4 sets of 15-20 repetitions.

- Rear Foot Elevated Split Squat

- Place your back foot on a couch or chair and once again aim for 3-4 sets of 15-20 repetitions.

This is a pretty challenging progression and I want to point a few things out:

- The exercises do not have to be performed linearly in this fashion. There are an infinite number of ways to work through a squat progression.

- Some may need assistance such as a handhold for the split squats while others find the split squats completely unnecessary for their goals.

- There are likely other exercises that would be performed alongside this progression as well.

- You can add weight to any of these movements.

I wanted to emphasize those points because you’re not going to be performing rear foot elevated split squats before you’re ascending and descending stairs. Remember, this is a guideline, not a protocol. When you do incorporate step up/down exercises, these are the three you should include:

Similar to the squatting variations, these need to be slow and controlled. If a normal step is too high, start on a 2 inch object (maybe a book). Then a 3 inch object. Then work your way up. Use a stick, handrail, or wall for balance. Eventually aim for 3-4 sets of 15-20 repetitions on a normal step without the use of your hands and your single leg control will be solid!

We have three exercises so far: walking, squats, and step ups/down. How might this look in action after a few months?

- Tuesday/Thursday/Saturday/Sunday – Three 1 mile walks

- Monday – 1 mile walk, 3×15 rear foot elevated split squats, and 3×15 lateral step down

- Wednesday – 1 mile walk, 3×15 forward step down, 3×15 step up

- Friday – 1 mile walk, 3×15 rear foot elevated split squats, and 3×15 lateral step down

Many individuals likely weren’t even doing this level of activity prior to their hip replacements so I stand by saying that this can take your functional capabilities pretty far. You’ll regain a lot of range of motion, balance, and strength by doing these movements and your other day-to-day activities. However, here are other progressions/exercises to consider:

- Cycling (recumbent or upright). Stationary to start! Wait for your doctor’s permission before riding outdoors. This usually feels great for people.

- Bridge/Hip Thrusts. Excellent way to strengthen the glutes while stretching the front of the hip. I’ve attached the entire playlist for each.

- Double Leg Bridge

- Double Leg Bridge with Band

- Single Leg Bridge

- Double Leg Hip Thrust

- Double Leg Hip Thrust with Band

- Single Leg Hip Thrust

- Deadlifts

- Planks

- Side Planks

- Isolated Adductor (Groin) Strength

- Isolated Hip Abductor (Glute) Strength

- Isolated Hip External Rotation (Glute) Strength

I only listed the playlists for several of these exercise categories because every total hip replacement protocol will outline the basic quad sets, glute sets, leg raises, hip ranges of motion, and the like. They’re not too complicated. It’s hard to give specific exercise parameters because everyone will be unique. I do think it’s important to perform a combination of compound and isolation movements. If you aim for 3-4 sets of 10-20 reps or 15-60 second holds, you’re in the right ballpark. All you have to do is make sure the exercise is sufficiently challenging and it’s tolerable for you based on the initial guidelines.

As I alluded to during the discussion of my own experience, rehabilitation isn’t just about enhancing your physical prowess. It’s about building confidence and self-efficacy, reducing stress and anxiety, and overcoming the fears and challenges that come along with having a total hip replacement. It took me a very long to get where I’m at today. It required a lot of trial and error to determine what works best for my physical and mental well-being. We’ll explore this a bit in the final section.

Return to High Level Activities

“Will I be able to lift weights?” It’s one of the few questions I remember asking my surgeon. He told me that I would be fine squatting up to 135 pounds because there were individuals much heavier than me who put that amount of stress on their implant with their normal day-to-day activities (I probably weighed 135 pounds at the time). That made sense to me. He told me that I could be active like a healthy young adult. He wasn’t encouraging or expecting me to go out and play tackle football, but I think he was giving me the freedom to be responsible with my choices. We also talked about some of the risks associated with high-impact activities. The only thing I distinctly remember him telling me to avoid was bringing my right knee beyond my left shoulder to minimize my risk for dislocation (which I can’t do anyway).

Here’s a short list things of things I’ve done since my total hip replacement:

- Hiked all 22 miles of Mt. Whitney (14,505’ elevation) in one day. I’m in the middle (pic above).

- Wrestling and boxing

- Basketball, soccer, flag football, softball, ultimate frisbee, tennis, volleyball

- Yoga, paddleboarding, skateboarding, ice skating

- Skydiving, mountain biking, rock climbing, snowboarding, cliff jumping

- Deadlift 2x bodyweight for 10+ repetitions

- Bulgarian split squat 185 pounds for sets of 3

Are these amazing feats of strength, skill, or endurance? Not for many, but it’s a glimpse into what can be done with an artificial hip.

Were all of these activities pain-free? No, but the discomfort of repetitive hip flexion as I ascended Mt. Whitney was worth the feeling of accomplishment at the top.

Do I still perform all of these activities? Yes and no. I’ll happily play sports on occasion, but I can’t bring myself to be as competitive as I used to be. I don’t jump as high for a rebound or run as fast to catch a frisbee.

I’ve decided that I’m going to lead an active, healthy lifestyle, but I’m going to do so while keeping my future in mind. There’s a lot of uncertainty about the longevity of the implant. If I can potentially extend the time until I need my first revision by minimizing high-impact activities, that’s what I’m going to do. It doesn’t negatively affect my quality of life.

I am not recommending that individuals with a total hip replacement perform any of the activities mentioned. I am simply describing my experience over the past 11 years. I will give my recommendations at the end, but we need to first examine the recommendations of surgeons.

In 2007, consensus guidelines for returning to athletic activity after total hip arthroplasty were published in The Journal of Arthroplasty based on surveys of the Hip Society and American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. Each activity was categorized by its impact level (high, intermediate, potentially low, low) and the group’s recommendation (allowed, not allowed, undecided, allowed with experience) [29]. Here’s a breakdown below.

- Allowed: doubles tennis, stairclimber, hiking, weight machines, low-impact aerobics, bowling, road cycling, rowing, speedwalking, dancing, pilates, golf, swimming, walking, stationary skiing, treadmill, stationary bicycle, elliptical machine

- Allowed with experience: downhill skiing, weight lifting, ice skating/rollerblading, cross-country skiing

- Undecided: Martial arts, singles tennis

- Not allowed: Racquetball/squat, jogging, contact sports, baseball/softball, high-impact aerobics, snowboarding

Most of the activities in the “allowed” group were classified as low-impact or potentially low-impact, although some activities like doubles tennis were deemed intermediate impact. On the other hand, most of the activities “not allowed” fall into the high-impact group. It’s important to understand that this was the general consensus. Some surgeons were more conservative while others were less conservative, with a very small percentage allowing activities such as jogging and high-impact aerobics [29].

Surgeons also varied in the length of time they recommended individuals wait before returning to activities after a total hip replacement. The majority recommended waiting 3-6 months and only 5.6% recommended waiting longer than 6 months. [29]. This would likely differ based on the chosen activity as walking.

A similar survey study of the British Hip Society was published in The Journal of Arthroplasty in 2017. Results were comparable except that surgeons were more permissive of activities which was a reflection of the change in their practice over the previous five years. For example, weight lifting (high weight/low reps) was allowed by 27.6% of surgeons and allowed with experience by 23.8%. Jogging on a treadmill was allowed by 32.4% and allowed with experience by 27.6%. The majority agreed that contact sports (75.2%), jogging on the road (59%), and martial arts (56.2%) were not allowed. For patients expecting to return to sporting activities, surgeons preferred ceramic-on-polytheylene or ceramic-on-ceramic bearing surfaces with the implant being uncemented or hybrid. Most surgeons recommended that patients wait 6-12 weeks (36.9%) or >12 weeks (43.7%) to return to sporting activities [30].

Do the data support the surgeons’ recommendations? Three studies in 2007, 2011, and 2012 would suggest that the concerns associated with high-impact activities may be warranted. Flugsrud et al. demonstrated that individuals with higher leisure time physical activity (as opposed to physical activity at work) had an increased risk of revision secondary to loosening of the acetabular cup [31]. Lübbeke and colleagues also showed higher rates of revision for aseptic loosening,and osteolytic lesions were more common in individuals partaking in greater amounts of activity [32]. Finally, Ollivier et al. reported greater wear and a higher number of revisions in participants engaging in high-impact sports [33]. The study calculated survivorship of the implant to be 93.5% in the low activity group and 80% in the high-impact sports group after 15 years [33]. An important thing to note is that the individuals in the high-activity groups, based on patient reported outcomes measures, had better clinical outcomes, function, and satisfaction compared to their less active counterparts [32,33].

Overall, the vast majority of individuals return to some level of physical activity; however, there is a significant decline in the amount of high-impact activities [34-38]. While some individuals do report pain with physical activity, the primary reasons for disengaging in sports include anxiety, insecurity, age-related loss of strength and function, and protection of the prosthesis [35,37]. There is a correlation with sports participation and motivation, and younger age and preoperative sports participation may help predict a successful return to activities [34,36]. Innmann et. al reported that 73% of patients return to sports in 6 months or less, while a systematic review by Hoorntje and colleagues showed that the average time frame was 7 months [35,36]. And to somewhat contrast the findings in the previous paragraph, Innman and colleagues showed that individuals partaking in high activity (but low-impact) did not negatively affect their implant survival after 11 years [35].

If you haven’t caught on yet, returning to sport safely is a very nuanced topic. Why? Recommendations might vary based on factors such as:

- Surgeon preference

- Cementless vs cemented vs hybrid

- Bearing surfaces

- Age

- Weight

- Preoperative activity levels

- Training history

- Goals

- Frequency, duration, and intensity of the sport

- And the list could go on for a very long time.

What are my specific recommendations? Well, one thing is not mentioned in any of these studies: return to sport criteria, or at least more stringent testing.

How do we determine if someone is ready to return to high level activity after a total hip replacement? It seems to be based on the passing of time and severity of symptoms. I don’t think that’s acceptable. We need objective data so we can appropriately prepare people for the demands of their sports.

We need to test and progress things like hip and thigh strength, running, and hopping/jumping. This isn’t about high-impact activity being safe or not. It’s about making sure you’re as ready as possible for it if that’s your goal.

Now, should you return to high-impact exercise? I think that’s a discussion to be had with your surgeon, physical therapist, and family. Is the risk of possibly needing an earlier revision worth the 10 years of marathons in the prime of your life? You might say yes. As I mentioned earlier, it’s not worth the risk for me anymore. My goals have changed and I’ve come to accept that.

If you had no goals in mind and just wanted to be as healthy as possible, I would recommend a wide range of exercise: walking, cycling, hiking, resistance training, etc. Most people are not meeting physical activity guidelines as it is and it’s one of the healthiest things you can do for yourself, so the last thing I want to do is discourage people from exercising. I train hard consistently while staying on the low-impact side of things with very minimal pain.

So… can you return to high level activities? Absolutely. Should you return to preoperative amounts of high-impact activities? It’s not a black and white, yes or no answer. It’s grey. It’s complex. I don’t think there is one right answer. We’ll see how my hip is doing in another 11 years.

If you somehow made it all the way through to the end, thank you for very much for reading. If you have any questions, just leave them in the comments below or shoot us an email. I’ll be happy to answer. And yes, metal detectors go off at the airport.

Don’t forget to check out our Hip Resilience Program!

Want to learn more? Check out the videos below or some of our other similar blogs:

Femoralacetabular Impingement (FAI), Gluteus Medius Training, Hip Flexor Stretches

References

- Cohen-Rosenblum A, Cui Q. Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head. Orthop Clin North Am. 2019;50(2):139-149.

- Liu L-H, Zhang Q-Y, Sun W, Li Z-R, Gao F-Q. Corticosteroid-induced Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head: Detection, Diagnosis, and Treatment in Earlier Stages. Chin Med J . 2017;130(21):2601-2607.

- Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. The Lancet. 2007;370(9597):1508-1519. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60457-7

- Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected Volume of Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(17):1455-1460.

- American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR): 2019 Annual Report. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), 2019.

- NJR. 16th Annual Report. 2019. London: National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Isle of Man, 2018.

- Gademan MGJ, Hofstede SN, Vliet TP, Rob G H, de Mheen PJM. Indication criteria for total hip or knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis: a state-of-the-science overview. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2016;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12891-016-1325-z

- Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1745-1759.

- Sansom A, Donovan J, Sanders C, et al. Routes to total joint replacement surgery: patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of need. Arthritis Care Res . 2010;62(9):1252-1257.

- Wang Z, Bao H-W, Hou J-Z. Direct anterior versus lateral approaches for clinical outcomes after total hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):63.

- Brrett WP, Turner SE, Leopold JP. Prospective randomized study of direct anterior vs postero-lateral approach for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9):1634-1638.

- Wang Z, Hou J-Z, Wu C-H, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of direct anterior approach versus posterior approach in total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):229.

- Aggarwal VK, Elbuluk A, Dundon J, et al. Surgical approach significantly affects the complication rates associated with total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B(6):646-651.

- Fleischman AN, Tarabichi M, Magner Z, Parvizi J, Rothman RH. Mechanical Complications Following Total Hip Arthroplasty Based on Surgical Approach: A Large, Single-Institution Cohort Study. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2019;34(6):1255-1260. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.029

- Coenders MJ, Mathijssen NMC, Vehmeijer SBW. Three and a half years’ experience with outpatient total hip arthroplasty. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2020;102-B(1):82-89. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.102b1.bjj-2019-0045.r2

- Goyal N, Chen AF, Padgett SE, et al. Otto Aufranc Award: A Multicenter, Randomized Study of Outpatient versus Inpatient Total Hip Arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2017;475(2):364-372. doi:10.1007/s11999-016-4915-z

- Berend KR, Lombardi AV, Berend ME, Adams JB, Morris MJ. The outpatient total hip arthroplasty. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2018;100-B(1_Supple_A):31-35. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.100b1.bjj-2017-0514.r1

- Monsef JB, Parekh A, Osmani F, Gonzalez M. Failed Total Hip Arthroplasty. JBJS Reviews. 2018;6(11):e3. doi:10.2106/jbjs.rvw.17.00140

- Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000435. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435

- Bayliss LE, Culliford D, Monk AP, et al. The effect of patient age at intervention on risk of implant revision after total replacement of the hip or knee: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1424-1430.

- Evans JT, Evans JP, Walker RW, Blom AW, Whitehouse MR, Sayers A. How long does a hip replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. The Lancet. 2019;393(10172):647-654. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31665-9

- Carli AV, Poitras S, Clohisy JC, Beaulé PE. Variation in Use of Postoperative Precautions and Equipment Following Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Survey of the AAHKS and CAS Membership. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3201-3205.

- Gromov K, Troelsen A, Otte KS, Ørsnes T, Ladelund S, Husted H. Removal of restrictions following primary THA with posterolateral approach does not increase the risk of early dislocation. Acta Orthopaedica. 2015;86(4):463-468. doi:10.3109/17453674.2015.1028009

- van der Weegen W, Kornuijt A, Das D. Do lifestyle restrictions and precautions prevent dislocation after total hip arthroplasty? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(4):329-339.

- Rowan FE, Benjamin B, Pietrak JR, Haddad FS. Prevention of Dislocation After Total Hip Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2018;33(5):1316-1324. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.047

- Moyer R, Ikert K, Long K, Marsh J. The Value of Preoperative Exercise and Education for Patients Undergoing Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JBJS Rev. 2017;5(12):JBJS Rev. 2017;5(12):e2.

- Austin MS, Urbani BT, Fleischman AN, et al. Formal Physical Therapy After Total Hip Arthroplasty Is Not Required. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2017;99(8):648-655. doi:10.2106/jbjs.16.00674

- Coulter C, Perriman DM, Neeman TM, Smith PN, Scarvell JM. Supervised or Unsupervised Rehabilitation After Total Hip Replacement Provides Similar Improvements for Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2017;98(11):2253-2264. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2017.03.032

- Klein GR, Levine BR, Hozack WJ, Strauss EJ, D’Antonio JA, Macaulay W, Di Cesare PE. Return to athletic activity after total hip arthroplasty. Consensus guidelines based on a survey of the Hip Society and American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22: 171-175 [PMID: 17275629 DOI: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.09.001]

- Bradley BM, Moul SJ, Doyle FJ, Wilson MJ. Return to Sporting Activity After Total Hip Arthroplasty-A Survey of Members of the British Hip Society. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(3):898-902.

- Flugsrud GB, Nordsletten L, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Meyer HE. The effect of middle-age body weight and physical activity on the risk of early revision hip arthroplasty: a cohort study of 1,535 individuals. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(1):99-107.

- Lübbeke A, Garavaglia G, Barea C, Stern R, Peter R, Hoffmeyer P. Influence of patient activity on femoral osteolysis at five and ten years following hybrid total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(4):456-463.

- Ollivier M, Frey S, Parratte S, Flecher X, Argenson J-N. Does impact sport activity influence total hip arthroplasty durability? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(11):3060-3066.

- Bonnin MP, Rollier J-C, Chatelet J-C, et al. Can Patients Practice Strenuous Sports After Uncemented Ceramic-on-Ceramic Total Hip Arthroplasty? Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(4):2325967118763920.

- Innmann MM, Weiss S, Andreas F, Merle C, Streit MR. Sports and physical activity after cementless total hip arthroplasty with a minimum follow-up of 10 years. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(5):550-556.

- Hoorntje A, Janssen KY, Bolder SBT, et al. The Effect of Total Hip Arthroplasty on Sports and Work Participation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018;48(7):1695-1726.

- Ortmaier R, Pichler H, Hitzl W, et al. Return to Sport After Short-Stem Total Hip Arthroplasty. Clin J Sport Med. 2019;29(6):451-458.

- Jassim SS, Tahmassebi J, Haddad FS, Robertson A. Return to sport after lower limb arthroplasty – why not for all? World J Orthop. 2019;10(2):90-100.