Whether you’ve had an ACL Reconstruction or you’re a clinician working with patients after an ACL Reconstruction, this blog will teach you about commonly held beliefs related to ACL surgery, the average rates of return to sport, and potential risk factors associated with a second injury.

Commonly Held Beliefs and Expectations

Prior to undergoing an ACL Reconstruction, most athletes have certain expectations regarding their future level of function and their time to return to sport after surgery.

For example, Feucht et al in 2016 found that in a preoperative group of athletes undergoing surgery for the first time (known as a primary ACL Reconstruction), or the second time on the same leg (known as a revision), all of the athletes expected a normal or near normal condition of their knee, and two-thirds expected a return to sport at the same level as prior to their injury without any restrictions.

In a study by Webster et al in 2019 that also recorded preoperative return to sport expectations, the researchers found that “91% of the cohort expected to return to sport, and 84% expected to return to their same pre-injury level.” These expectations were lower, on average, in the second primary procedure (which is an ACL Reconstruction on the other knee) and revision groups. Additionally, athletes under 20 years of age reported slightly higher expectations of returning to sport compared to athletes over 20 years of age.

Armento et al in 2020 provided adolescent athletes (who were 12-18 years old) with a resource guide prior to undergoing surgery. This guide stated that athletes should expect to be out of sport for a minimum of 6 months, with an average return to sport clearance of 9-12 months. Even with this information provided, the authors found that “the majority of our adolescent population expected to return to sport after ACL reconstruction far sooner than the expected timelines, indicating potential unrealistic pre-operative expectations.”

A significant proportion of athletes expect a normal or near normal condition of their surgical knee, a full return to sport at the same level or higher as prior to their injury, and a full return to sport in the shortest time possible, but how often are these expectations lining up with reality?

Expectation vs Reality: Return To Sport Rates

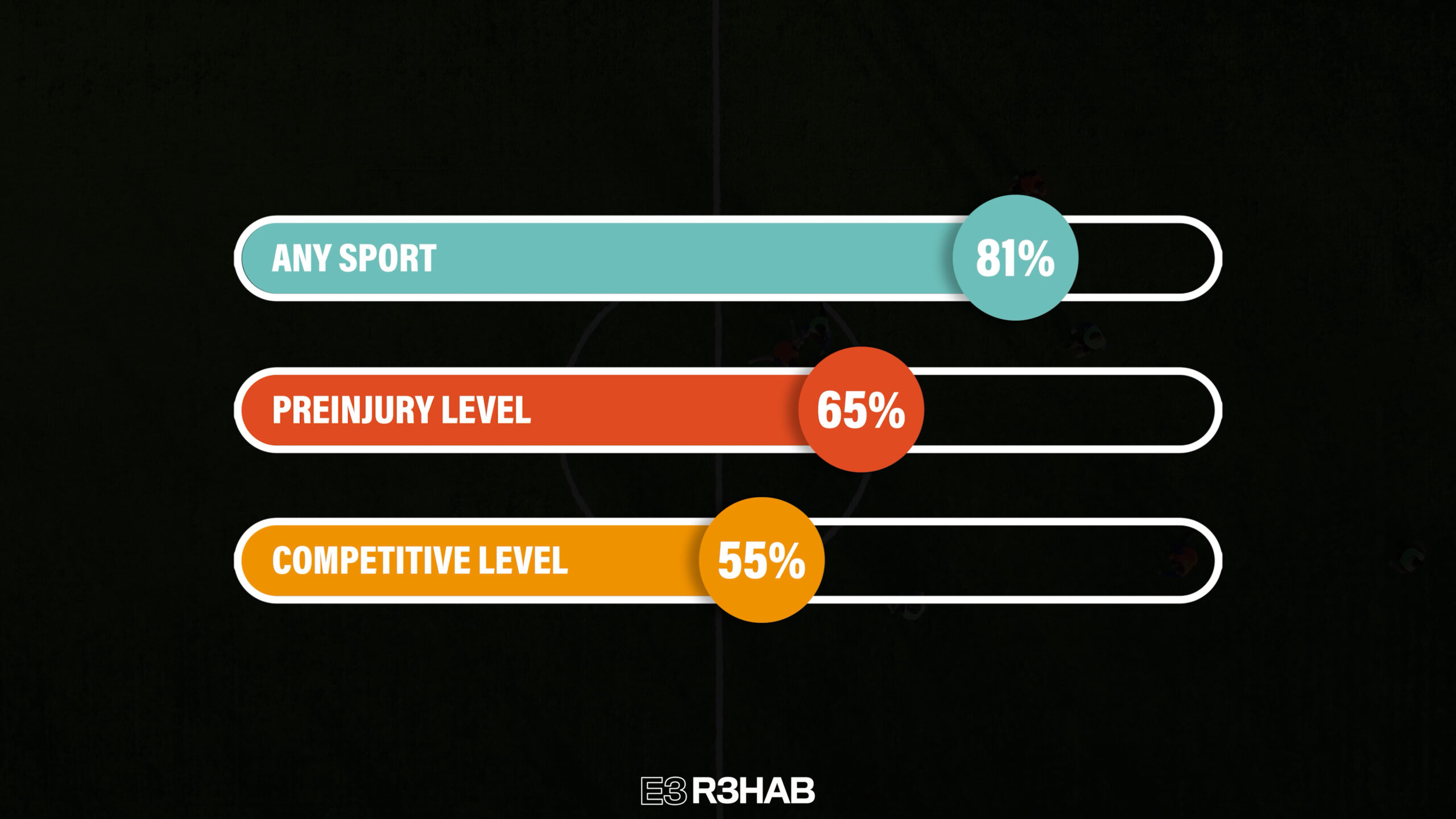

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Ardern et al in 2014 investigating return to sport outcomes in athletes after ACL Reconstruction found that 81% of athletes returned to any sport, 65% returned to their preinjury level of sport, and 55% returned to their competitive level of sport.

The authors did not clearly define the differences between preinjury level of participation and competitive sport. However, it’s fair to assume that an athlete’s preinjury levels (at least within the included studies in this review) ranged between recreational and competitive sport. Although a large number of athletes undergoing primary ACL Reconstruction return to some level of sport participation, this review indicates that roughly only half return to competitive sport.

DeFazio et al in 2020 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing return to sport rates between athletes receiving hamstring tendon versus bone patella tendon bone ACL grafts. The authors of this review state that “regardless of the graft type, less than half of the athletes returned to sport at the preinjury level after the primary ACL reconstruction.”

Returning back to the cohort presented by Webster et al in 2019 – out of the initial 84% of athletes expecting to return back to their same preinjury level, only 24% actually met that expectation at the 12 month mark. However, because this information was collected at 12 months out from surgery, a greater number of athletes might have returned to sport at their preinjury level beyond this 1 year timeline.

It is also worth noting that 15% of this entire cohort, including a combination of primary, contralateral (which is a first time injury to the opposite knee), and revision surgeries, gave up sport by 12 months. Of those athletes that gave up sport, 71% reported fear of reinjury as their main reason for not returning.

Ultimately, it is up to the athlete’s orthopedic and rehabilitation teams to set appropriate expectations for patients, their family members, coaches, and all other key stakeholders leading up to a primary ACL Reconstruction. Outside of presenting patients with the data on average return to sport (and return to prior level of competition) rates, it is paramount for patients to understand the risk factors associated with, and the probability of, a second ACL injury.

In the next section, I will cover both re-tear rates of the surgical limb and the contralateral knee following initial ACL Reconstruction.

What Are Your Chances of a Second ACL Injury?

A systematic review performed by Barber-Westin et al in 2020 found that, although roughly 80% of athletes post-ACL Reconstruction returned to some level of sport, 1 in 5 athletes sustained a reinjury to either knee.

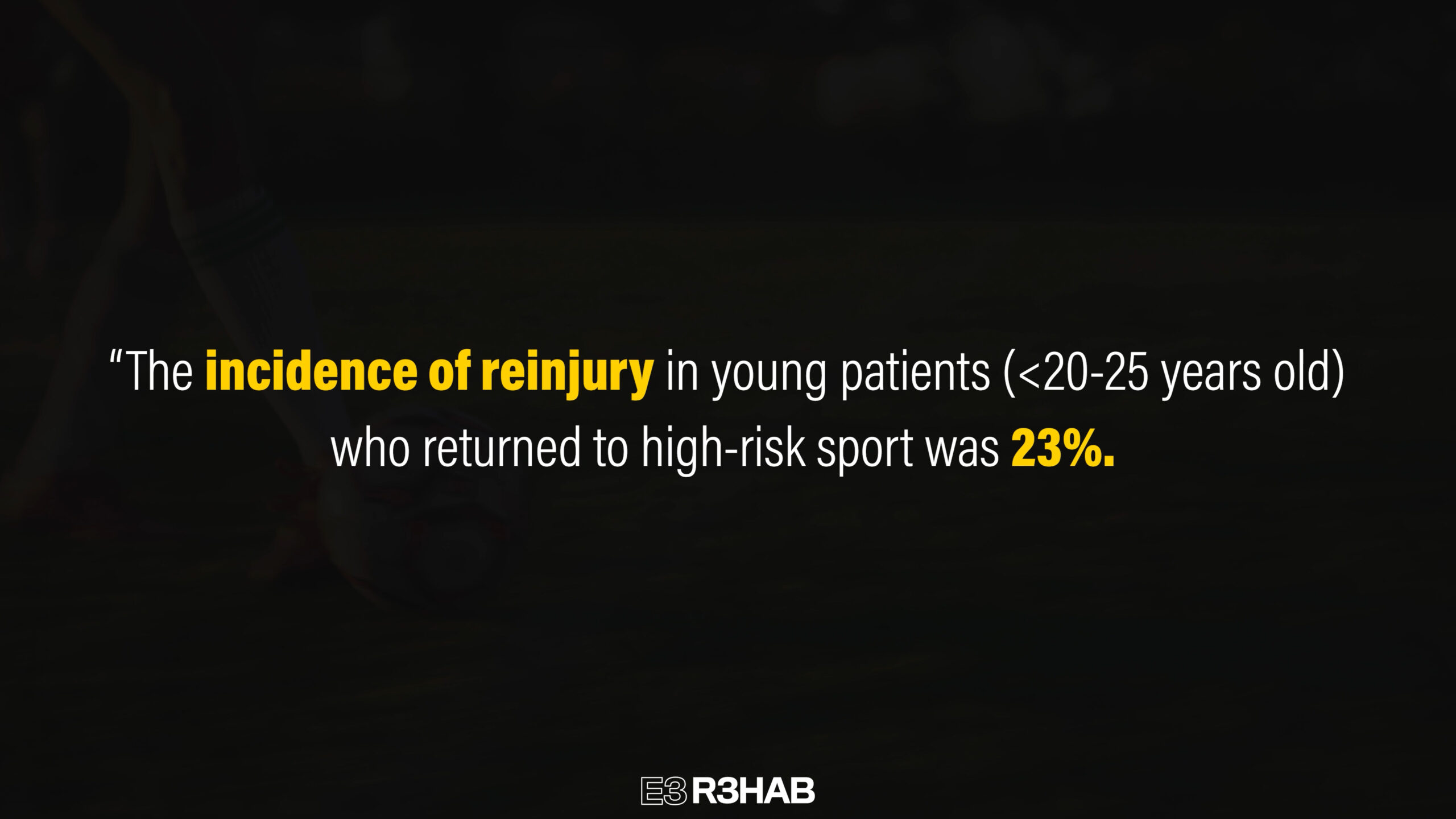

Another systematic review by Wiggins et al in 2016 reported that “the incidence of reinjury in young patients (<20-25 years old) who returned to high-risk sport was 23%. This means that nearly 1 in 4 young athletic patients who sustain an ACL injury and return to high-risk sport will go on to sustain another ACL injury at some point in their career, and they will likely sustain it early in the return to play period.”

Level 1 sport and high risk sports are defined as any sport involving hard pivoting, cutting, and jumping. Basketball, football, soccer, and skiing are examples of Level 1 sports that demonstrate the highest risk of second ACL injury.

A systematic review and meta-analysis performed by Kay et al in 2018 looked at children and adolescent return to sport rates following ACL Reconstruction. They reported: “The most significant finding in the present study was a very high rate of return to any sporting activity after ACL reconstruction in the pediatric population (92%), and a high rate of return to competitive level sports at the pre-injury level (81%). Unfortunately, this was associated with a relatively high graft rupture rate (13%) and injury to the contralateral ACL (14%).”

Although over 80% of these athletes returned to their pre-injury level, close to 1 out of every 3 athletes suffered a second ACL injury. The authors go on to note that, “the high rate of graft or contralateral ACL rupture following ACL reconstruction in this age group (close to 30% combined) highlights an important concern during rehabilitation for this population.”

What Factors Increase The Chance of a Second ACL Injury?

There are a host of risk factors contributing to why athletes may sustain a second ACL injury, but I’m going to review some of the most commonly researched and discussed factors.

Return To Level 1 Sports

Returning to level 1 sport after ACL Reconstruction is the highest risk factor for sustaining a second ACL injury. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Cronstrom et al in 2021 reports that “return to high activity level was the most prominent risk factor for sustaining a contralateral secondary ACL injury.”

Additionally, the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study by Grindem et al in 2016 noted that “the knee reinjury rate was over four times higher in ACL reconstructed patients who returned to level 1 sports after surgery” compared to those who did not return.

Why are Level 1 sports the number one risk factor?

These sports provide the most frequent exposure to specific joint angles and forces that are known mechanisms of ACL injury. These joint angles include, shallow knee and hip flexion, internal tibial rotation and forward translation, knee valgus, and lateral trunk and knee abduction. An ACL injury most commonly occurs in these specific joint angles during deceleration (slowing down) and/or direct contact/collision with another athlete.

Early Return To Sport

Grindem et al in 2016 report that “During the first nine months after surgery, a later return to sport was significantly associated with a lower reinjury rate. For every month of delay in return to sport, the reinjury rate was reduced by 51%.” “Patients who participated in level 1 sports earlier than nine months after surgery sustained 39.5% reinjuries, compared to 19.4% knee reinjuries in those who returned to level 1 sports later than nine months after surgery.”

Beischer et al in 2020 found that “athletes who had returned … before 9 months after reconstruction had an approximately 7-fold higher rate of second ACL injury compared with those who returned at 9 months or later.”

It was noted by Grindem et al in 2016 that “the increased risk could be due to insufficient biologic healing (e.g. grafter incorporation and remodeling), incomplete rehabilitation, or both.”

From a timeline perspective, waiting at least 9 months for a full return to sport appears to provide the greatest likelihood of minimizing the risk of a second injury. Although there are rare outliers (such as Adrian Peterson) who return to (and excel in) sport earlier than 9 months, trying to rush this process and accelerate a faster return prior to 9 months should not be the goal for the vast majority of athletes. There should be adequate time for maturation of the graft in addition to sufficient time spent progressively preparing the athlete for the demands of their desired sport.

Age

Individuals who are younger than 20 years old have significantly higher reinjury rates compared to older individuals. Before proceeding, it should be noted that younger age in and of itself is not a causal risk factor for a second ACL injury. Return, and more frequent exposure to high risk activities or level 1 sport is the primary risk factor. It just so happens that individuals younger than 20 years old are most likely to return back to a high risk sport or activity.

As I mentioned earlier, the systematic review by Barber-Westin et al in 2020 discovered that “a high rate of athletes <20 years old returned to sport, but 1 in 5 suffered reinjuries to either knee, and the majority of these occurred during high-risk sports activities.”

Cronstrom et al in 2021 state the following: “The result from the present meta-analysis supports the findings of a previous review that reported an increased rate of secondary ACL injuries in individuals younger than 25 years. Similarly, we found the odds of sustaining a contralateral ACL injury in those younger than 18 and 20 years to be twice the odds of those older than 18 and 20 years, respectively.”

Andernord et al in 2015 concluded that “In both male and female participants, age <20 years predicted an almost 3 times higher 5-year risk of contralateral ACL reconstruction.”

I want to reiterate that participation in level 1 sport is the biggest risk factor for sustaining a second ACL injury, not age. It just so happens that individuals younger than 20 years old are most likely to participate in, and return back to, level 1 sport.

Female Sex

Female sex is commonly thought of as a high risk factor for second ACL injury, however this is not in line with the majority of the current evidence.

Patel et al in 2021 report that, “The results of this systematic review and primary meta-analysis determined that there is a negligible, non-statistically significant difference in the relative and absolute risk of experiencing a second ACL injury (both ipsilateral [same knee] and contralateral combined) between both sexes.” Stated more simply, males and females display similar chances of second ACL injury, both groups with over a 20% risk of re-injury.

Additionally, Keiding et al in 2015 state that, “although a strong predictor of native ACL injury, female sex was not found to be a risk factor for tear of an ACL graft in this cohort.”

Graft Type

Allografts (grafts from a cadaver) are reported to have higher re-rupture rates compared to autografts (grafts from an individual’s own body), as evidenced by the systematic review performed by Wasserstein et al in 2015.

In regards to differences between autograft types, Hamstring Tendon vs Bone Patella Tendon Bone vs Quadriceps Tendon, there are relatively similar rates of second injury or graft failure as noted by the systematic reviews and meta-analyses by Mouarbes et al in 2019, Dai et al in 2022, and Hayback et al in 2022.

Hayback et al in 2022 conclude that “… all these [autograft] graft options deliver comparable results in terms of graft failure rates and therefore every graft type could be rightly considered as a reliable option for ACL Reconstruction.”

Autografts are the superior option (over allografts) for those expecting to return back to activities involving high amounts of pivoting, cutting, sprinting, and jumping. Determining which autograft to use is largely dependent on surgeon preference and their training and exposure to a specific graft.

Quadriceps Strength and Return To Sport Testing

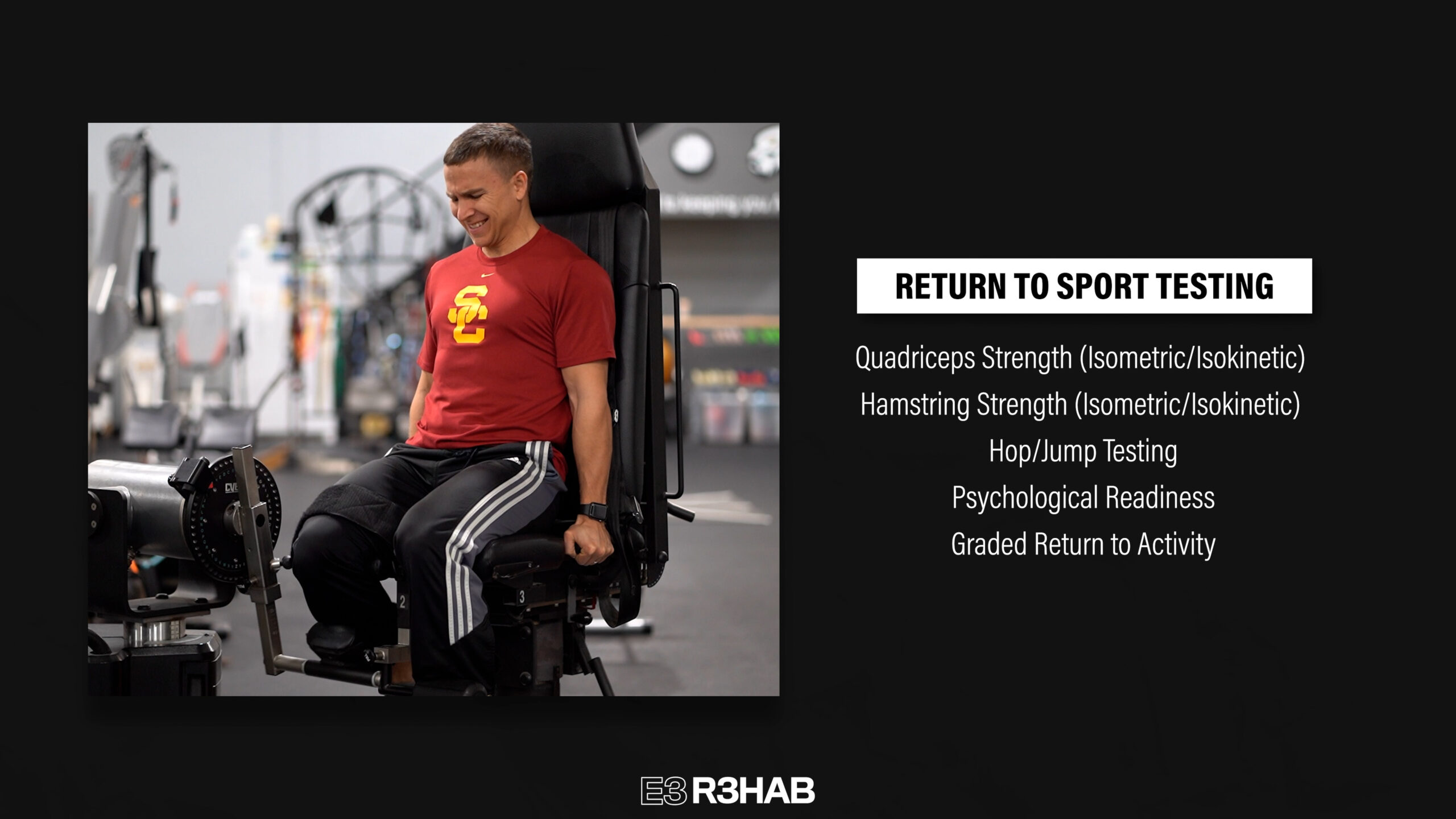

Although objective return to sport testing is necessary and highly recommended during the post surgical process, it is unclear whether a battery of return to sport testing significantly reduces the risk of a second ACL injury. Return to sport testing commonly consists of a combination of isometric and/or isokinetic quadriceps and hamstring strength assessments, hop and/or jump testing, psychological readiness, and a graded return to practice, sport, and competition.

There are multiple systematic reviews with mixed or conflicting findings on this topic. For example:

Losciale et al in 2019 state: “Passing return to sport criteria did not show a statistically significant association with a risk of a second ACL injury. The quality-of-evidence rating prevents a definitive conclusion on this question and indicates an opportunity for future research.”

Webster et al in 2019 write: “Passing return to sport test batteries did not significantly reduce the risk of further knee injuries in general or ACL injuries specifically.”

Welling et al in 2020 report that passing RTS tests can increase the chances of return to sport, but does not determine the likelihood of secondary ACL injuries.

However, there are a handful of papers, including Grindem et al in 2016, arguing for the importance of assessing quadriceps strength as a key factor for determining risk of secondary ACL injuries. To further add to the uncertainty, Capin et al in 2019 wrote an editorial critiquing the claims and findings of the systematic review and meta-analysis by Webster et al in 2019 mentioned previously.

The most recent ACL Reconstruction Clinical Practice Guideline by Kotsifaki et al in 2023 notes that, “Currently, it is not clear if passing a battery of tests is associated with lower risk of second ACL injury.” The authors add that, “despite this caveat, we maintain that our clinical goals should be to restore all impairments and return the athlete back to the previous status, if not better.”

Return To Sport Decision Making

What’s the key takeaway from all of the murkiness just mentioned?

Even though it may not be completely clear how helpful return to sport testing is from the standpoint of predicting second ACL injuries, it is still incredibly important for assessing an athlete’s current capacities and readiness for progression in rehab and ultimate preparedness for the demands of their sport. This testing should occur throughout the ACL rehab process and should cover a variety of metrics including isolated quadriceps and hamstring strength and symmetry, psychological readiness (ACL RSI), jumping performance, and any other objective metric related to the demands of that athlete’s sport.

The most recent Clinical Practice Guideline by Kotsifaki et al in 2023 provides a detailed outline of recommendations for bare minimum testing results for both return to running and return to sport.

Can You Actually Prevent A Second ACL Injury?

As you hopefully discovered from this blog, there is no magic bullet or one specific thing to completely prevent a second ACL injury. Level 1 sport is inherently dangerous and injuries will never fully disappear. Athletes should be aware of and accept that returning back to Level 1 sport is the biggest risk factor for sustaining a second ACL injury.

In order to best prepare an athlete for returning to Level 1 sport, these are the 5 things that should occur:

- Wait at least 9 months for a full return.

- Complete a progressive and adequately demanding rehab and training program during these 9+ months.

- Frequently assess the limb and entire athlete’s capacities and qualities necessary for successful performance through a battery of return to sport tests.

- Complete a graded return to practice, sport, and competition based program.

- Demonstrate psychological preparedness and confidence for a full return back to sport.

Summary

Here are the 8 main takeaways from this blog:

- High patient expectations may not match the reality of average return to prior level of injury and competition rates after primary ACL Reconstruction.

- Roughly two-thirds of primary ACL Reconstruction athletes return to their prior-level of sport and half return to a competitive level.

- On average, 20-30% of athletes returning to sport will suffer a second ACL injury.

- Return to Level 1 sport is the strongest predictor of experiencing a second ACL injury.

- Younger populations are at elevated risks due to the nature of this group having the largest probability of returning back to Level 1 sport.

- Female sex is not a risk factor for a second ACL injury.

- Allografts, compared to autografts, demonstrate larger rates of re-rupture and second ACL injury. Autografts, quadriceps tendon vs hamstring tendon vs bone patella tendon bone, are relatively similar in terms of average re-rupture rates, and are highly utilized and recommended (over allografts) for younger, active populations undergoing ACL Reconstruction.

- A battery of return to sport testing has mixed results in regards to significantly reducing the risk of a second ACL injury. However, objective testing should be used throughout the rehab process to determine readiness and progression of rehab and guide decision making for appropriate reintegration to sport participation, play, and competition.

Want to learn more? Check out some of our other similar blogs:

ACL Rehab, Leg Extensions After ACLR, ACL Plyos

Thanks for reading. Check out the video and please leave any questions or comments below.