The purpose of this blog is to discuss lumbar spinal stenosis and provide a comprehensive framework for rehab, including exercise progressions with sets and reps.

Do you have new, lingering, or recurring low back pain that’s stopping you from doing the things you enjoy or keeping you from feeling like yourself? Check out our Low Back Resilience Program!

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

The spine is comprised of different regions:

- The cervical spine, which is your neck.

- The thoracic spine, which is your upper and middle back.

- And the lumbar spine, which is your lower back and the area we’re interested in for this blog.

- There’s also the sacrum and coccyx at the base.

Part of the spine’s purpose is to house and protect the spinal cord and its associated nerves.

In most cases of lumbar spinal stenosis, it’s a degenerative process, associated with aging, that can negatively affect the spinal cord or nearby nerves. Stenosis means narrowing, so lumbar spinal stenosis is narrowing of those nerve spaces in the lumbar spine.

Associated symptoms may include butt or leg pain with standing or walking, and relief of that pain with sitting or bending forward. The thought is that being more upright, such as in standing and walking, may reduce the amount of space for those nerves. You might also notice tingling, weakness, and a wider base of support when walking.

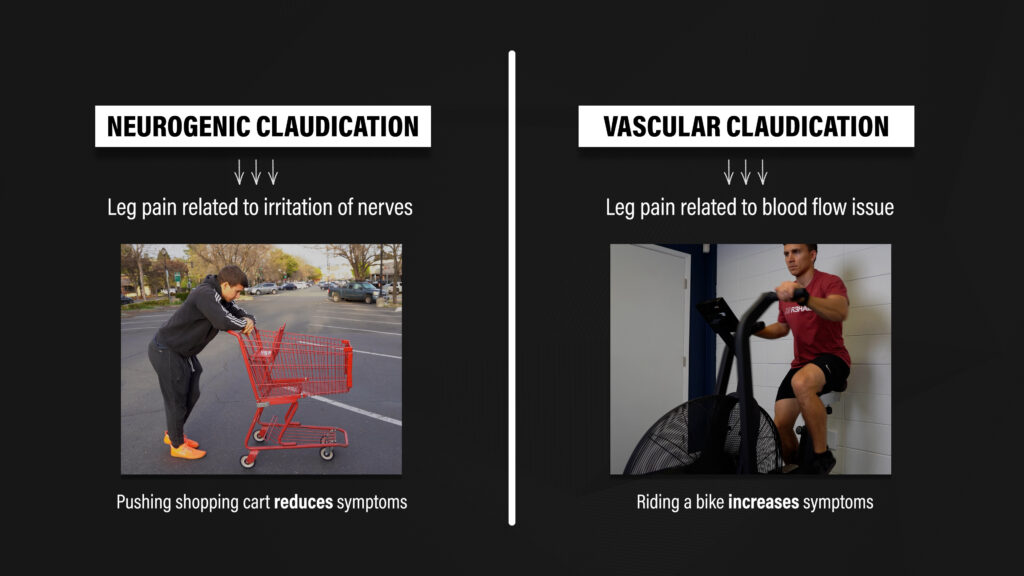

A medical doctor may describe these symptoms as neurogenic claudication, which is pain in the legs related to irritation of nerves. This is different from vascular claudication, which is a blood flow issue.

The “shopping cart sign” is used to differentiate the two. If someone has pain in their legs during walking that’s associated with lumbar spinal stenosis, then bending forward to push a shopping cart should alleviate symptoms. Another distinguishing feature is that riding a bike would worsen vascular claudication, but not neurogenic claudication.

Cook et al 2010 Suri et al 2010 Schepper et al 2013 Tomkins-Lane et al 2016

Exercise Rationale

If lumbar spinal stenosis is a degenerative condition associated with structural changes, how can exercises help? Why not jump straight to surgery and fix the issue?

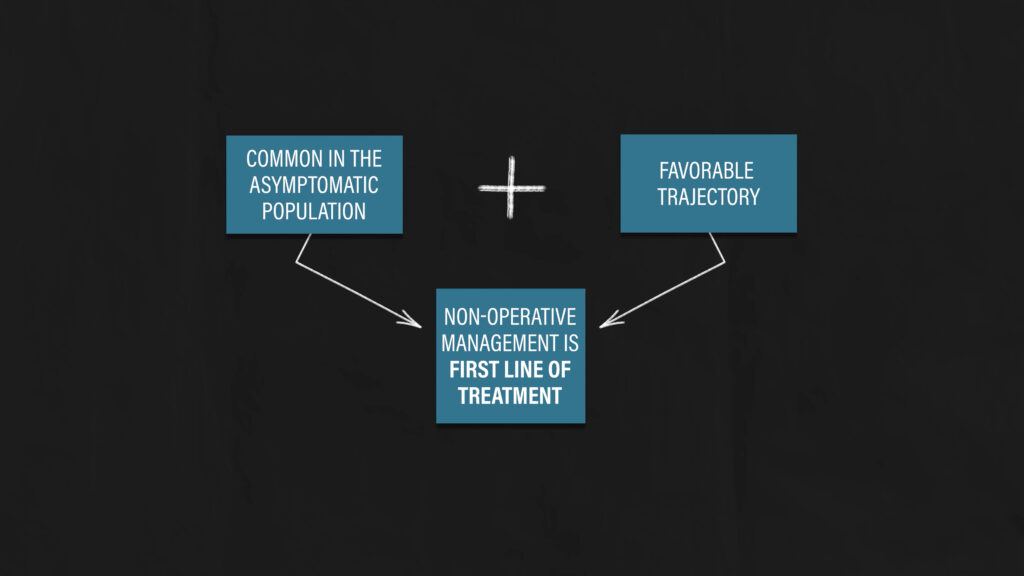

Well, a systematic review by Jensen et al in 2020 found that 21-33% of individuals over the age of 60 have no symptoms despite demonstrating lumbar spinal stenosis on imaging. Similarly, Wesberg and Frennered in 2017 found a poor relationship between most findings on imaging and symptoms. Lastly, Haig et al in 2006 concluded that “the impression obtained from an MRI scan does not determine whether lumbar stenosis is a cause of pain.”

Based on this information, a recent paper in the British Medical Journal by Jensen et al in 2021 suggests that “imaging is not required during initial assessment as the correlation between imaging findings and symptoms is poor.” The authors also recommend non-operative management as the first line of treatment.

Therefore, the purpose of exercise isn’t to change the structure of your spine on imaging. The goal is to gradually improve your function and quality of life.

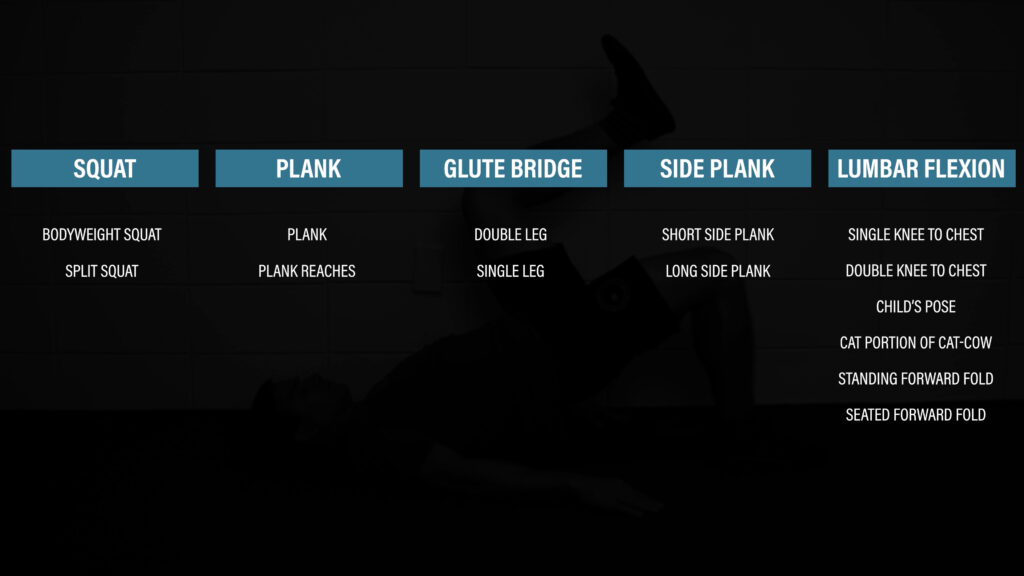

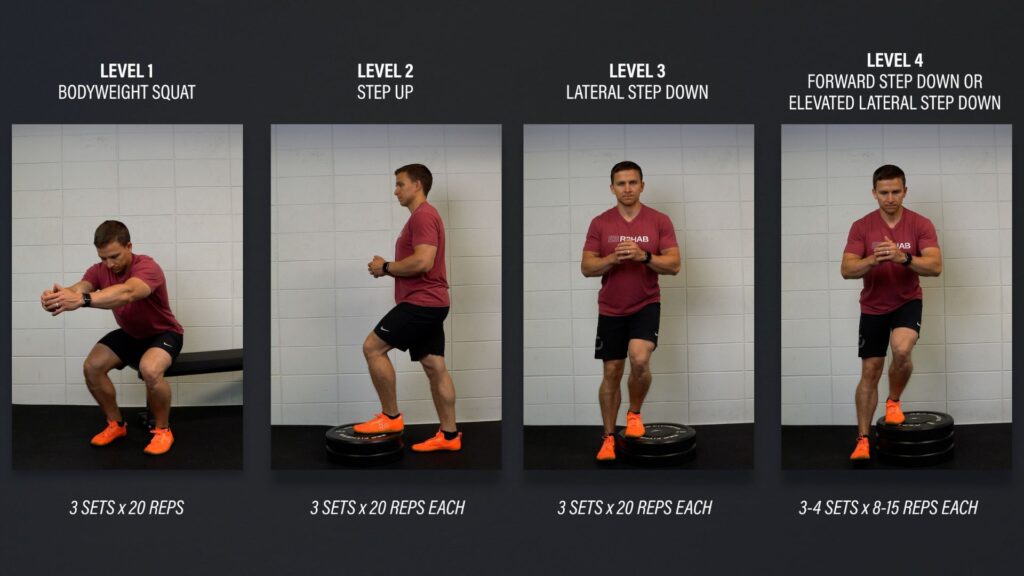

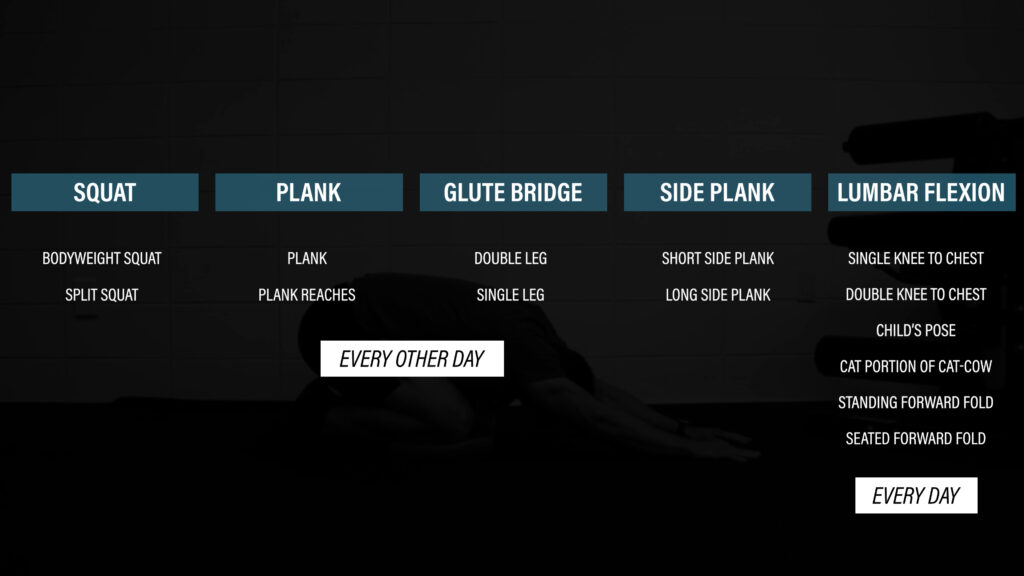

Exercise #1: Squat Progression

Level 1 – Bodyweight Squat. Gently tap your butt to a chair and stand back up. If it’s too challenging or painful, shorten the range of motion or use your hands for assistance. Aim for 3 sets of 12-15 repetitions.

Level 2 – Split Squat. Start in a stride stance, lower yourself straight down so that your back knee taps an egg that you don’t want to crack, and then stand back up. Shorten the range of motion and/or use your hands for balance if it’s too challenging. Aim for 3 sets of 6-12 reps.

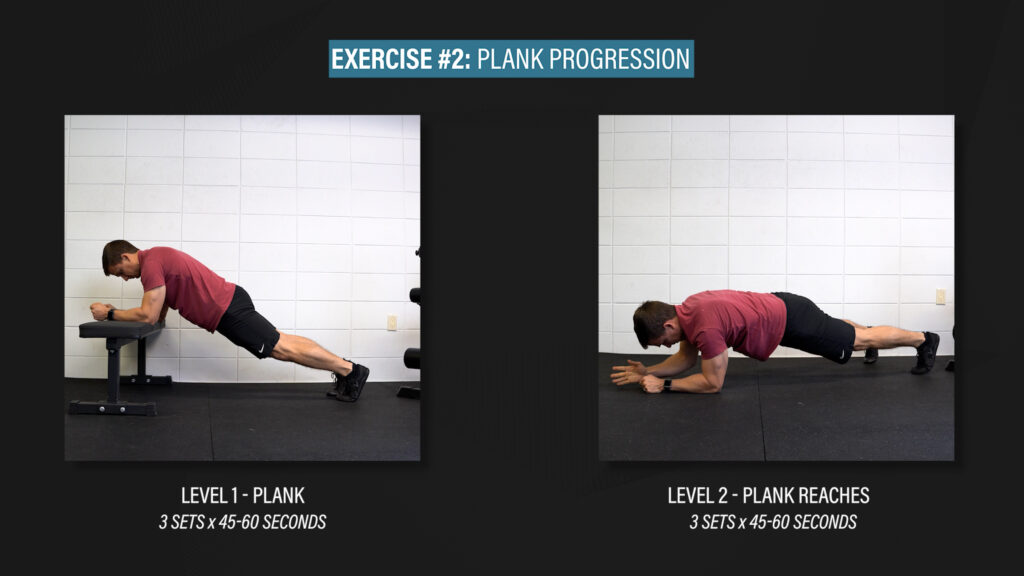

Exercise #2: Plank Progression

Level 1 – Plank. Set up on your toes and forearms with your elbows under your shoulders. Keep your body in a straight line as you squeeze your butt muscles as hard as you can. If it’s too difficult, you can start on an elevated surface.

Level 2 – Plank Reaches. You’ll still be holding a plank, but you’ll alternate reaching your arms out in front of you, only as far as you can comfortably go while maintaining your trunk position.

Aim for 3 sets of 45-60 seconds as you work through each exercise.

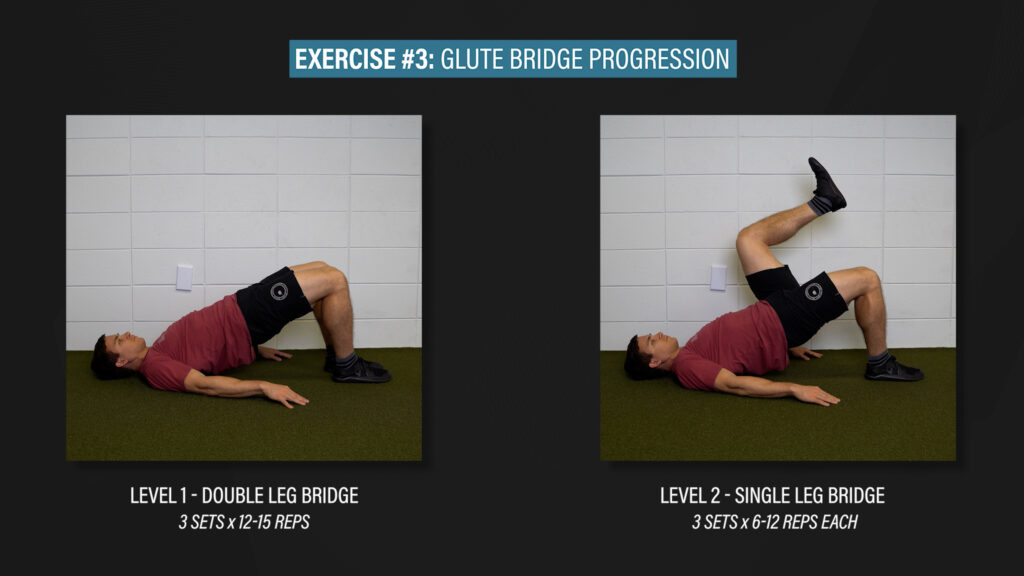

Exercise #3: Glute Bridge Progression

Level 1 – Double Leg Bridge. Lie on your back, bridge up, squeeze your glutes, and lower back down. Aim for 3 sets of 12-15 reps.

Level 2 – Single Leg Bridge. You can keep the opposite knee straight or bent. Aim for 3 sets of 6-12 reps.

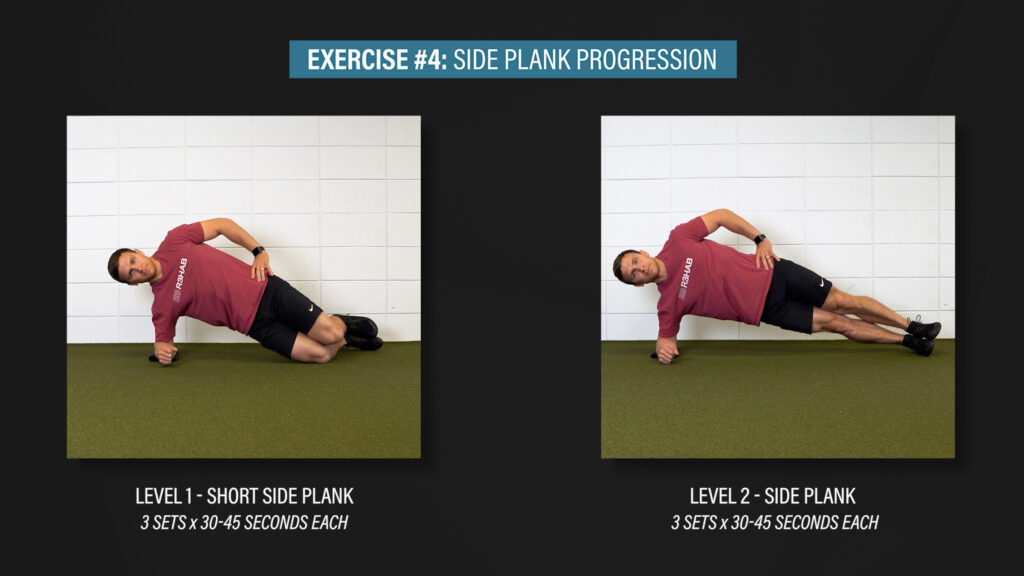

Exercise #4: Side Plank Progression

Level 1 – Short Side Plank. Start on your forearm and knees while keeping your trunk in a straight line.

Level 2 – Side Plank. Straighten your legs, stack your feet, and keep yourself in a straight line, both from a front view and top view.

Aim for 3 sets of 30-45 seconds as you work through each exercise.

Lumbar Flexion Exercises

Lumbar flexion exercises, which are intended to round the lower back, can also be used periodically throughout the day to alleviate symptoms. I’ll list them here and you can perform them as needed. There’s no specific sets and reps that you need to accomplish. Just find what feels good for you, while improving your function with the previously mentioned exercises.

Guidelines, Not Rules

Please recognize that these exercise recommendations are guidelines, not hard and fast rules. It’s always best to tailor an exercise routine to your individual needs and goals. For example, if you find that the side plank is too much for your shoulder or the single limb bridge is uncomfortable, you can choose not to do them and find similar movements that you prefer.

Maintaining Physical Activity

In addition to performing the exercises outlined, it’s important to maintain your physical activity levels to the best of your ability. If walking has become difficult, cycling or swimming can be great alternatives to stay active and minimize deconditioning.

And since symptoms will undoubtedly fluctuate over time, tracking your steps can be helpful to monitor progress. You can observe how you’re doing over the course of weeks, months, and even years, and try to increase your steps when possible.

When Should You Get Surgery?

I can’t give you a definitive answer, but I can provide you with information that you can take into consideration during that discussion with your medical doctor.

When comparing surgical and non-surgical outcomes, most individual studies tend to favor surgery in the first several years. However, a 2016 Cochrane Review, the gold standard for the appraisal of evidence, states that the authors “have very little confidence to conclude whether surgical treatment or a conservative approach is better for lumbar spinal stenosis.”

When examining the outcomes of the studies at 6, 8, and 10 years later, the benefit of surgery diminishes and results are similar between groups. But, in addition to surgery being more costly, up to 23% of people require a reoperation.

It’s also important to mention that no randomized, placebo-controlled trials that compare real surgery to fake surgery have been conducted yet, although one such study is under way.

Surgery may be indicated in some cases, such as when severe or progressive neurologic deficits are present, but non-operative management is usually the first recommendation.

If surgery is indicated, a randomized controlled trial in the New England Journal of Medicine by Forsth et al in 2016 suggests that fusions should be the exception rather than the norm.

Summary

In summary, lumbar spinal stenosis is a condition associated with symptoms in the butt or legs from standing or walking, and relief of those symptoms with sitting or bending forward. Since it is common in the asymptomatic population and has a favorable trajectory, non-operative management is recommended as the first line of treatment in the majority of cases.

Exercises should focus on improving function rather than trying to change the structure of your spine. Examples include squats, bridges, planks, and side planks, which can be performed every other day, or as tolerated. Additionally, exercises used to alleviate symptoms, such as a double knee to chest or child’s pose, can be incorporated into your daily routine as needed. Lastly, tracking steps and maintaining physical activity levels through cycling, swimming, or another means can be extremely beneficial.

Don’t forget to check out our Low Back Resilience Program!

Want to learn more? Check out some of our other similar blogs:

Spondylolisthesis, Lumbar Imaging, Scoliosis

Thanks for reading. Check out the video and please leave any questions or comments below.